In Mexico City, residents organised to convince the city government to build a public park instead of developing an area for office buildings. The Parque Imán can serve as an example for successfully greening neighborhoods, and reclaiming public space in a participatory and transparent manner. It is a very good example of how SDG 11 can be implemented.

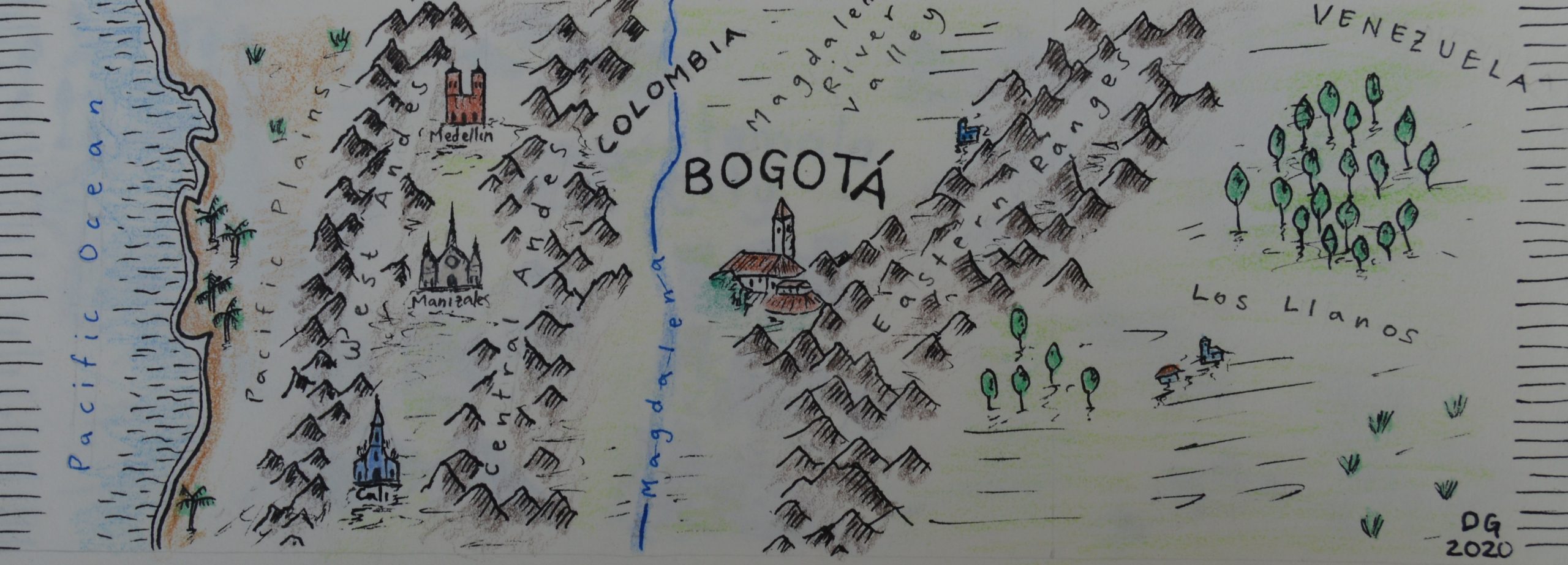

Mexico City might be known internationally for many things, such as criminality, air pollution and heavy traffic. Recently, it has been gaining a reputation for more positive aspects such as efforts undertaken to green the city and to improve air quality.

Having lived in this bustling metropolis for more than 1.5 years now, as an urban development student it struck me that the city has a special talent maybe unknown beyond its boundaries: the redevelopment and regeneration of public spaces.

Admittedly, most of these activities take place within the city center or in other popular and wealthier areas, but it is still contributing to making the city a greener, pedestrian-friendlier and more livable place overall. What is more, participatory processes for redevelopment are gaining ground. This article focuses on a big redevelopment project that turned part of an asphalt plant into a modern, beautiful park. The Parque Imán project was only finished a bit more than a year ago, in March 2018. Its participatory aspects, as well as the fact that it is located in an area of the city not predestined for government investment, make for a very interesting case.

The Asphalt Plant

Mexico City’s largest asphalt plant, the Planta de Asfalto, covers an area of 18 hectares. It was renovated recently for the first time since it was built in the 1950s in order to reduce air contamination and harmful emissions, which were cut by about 60 per cent.

At the same time, in mid-2014, Mexico City’s government had plans to reduce the size of the asphalt plant grounds and use the newly won space to create a “City of the Future”, the so-called Coyoacán Economic and Social Development Area. This plan entailed housing blocks and a high number of offices for scientific and technological researchers, which were expected to support the economic power of the district. However, residents of the neighborhood protested and formed groups such as “No al Ciudad del Futuro”. Nevertheless, at the end of 2014 the plant owner sold the land to the government.

Residents feared that the already very densely populated areas might be overrun by the new “City of the Future”. They worried about potential strains on infrastructure such as water supply and sewage systems, as well as increasing property taxes. Instead, they advocated a green space. This is a typical example of the struggle over space currently happening in Mexico City. Citizens become increasingly engaged in local grassroots organisations, interacting with the government and putting forward ideas for developing their neighborhoods.

In 2016, local deputies invited neighbors to a participatory public consultation to discuss the future of the available space that was formerly part of the asphalt plant. Together, they decided to abandon the “Future City” idea and instead suggested to create a park. Mexico City’s then-mayor, Miguel Ángel Mancera, was quoted describing the new park as a compromise that the government made with local residents in order to provide them with a green space, which they did not have before.

The Creation of Parque Imán

As a result of the residents’ protests and the public consultation, Parque Imán was created. Public pressure and the fact that residents’ associations were watching the process very closely assured participation and transparency. The most prominent organisation that took part in this consultation, “No al Ciudad Futuro”, is part of the neighborhood group “Community Action Pedregales”. This very active group connects local assemblies with each other and provides information through their website.

By creating public visibility, they were able to monitor the creation of the park closely and to publish all relevant documents along with comments. Regular meetings as well as the public consultation resulted in a transparent process that was (in theory) open to everyone — however, as it is often the case with participatory opportunities, it was mainly volunteers of the Community Action group and people with enough leisure time who could afford to follow the process and attend the meetings.

The park opened in March 2018. It currently covers 2.4 hectares of land, but will be enlarged over time by at least 10 additional hectares of the asphalt plant grounds, as the plant itself will close in the near future.

An investment of 150 million pesos (6.6 million Euros) was made by the city government to redevelop the space into a popular and modern park. Up to 200,000 residents of the boroughs of Coyoacán, Tlalpan, and Benito Juárez will benefit from this green space, which is the only one of its kind in the whole area apart from the university campus.

The design of Parque Imán is based on volcanic stone to support the local identity of the Pedregal de San Ángel area. The Pedregal is an area in the South of Mexico City’ that is characterized by black volcanic stone — a remainder of the eruption of the Xitle volcano some 1,700 years ago. The porous black stone is integrated into the park’s design. Parque Imán features playgrounds, a climbing wall, a skate park, benches, a stage, parking for cars and bicycles, and, very importantly, public bathrooms. Solar energy panels provide power to lamps that light up the park at night-time, and two murals created by Mexican artists adorn several walls built within the park, adding an important element of Mexican identity and typical national art.

In total, 163 trees as well as tens of thousands of bushes and plants have been planted in the park, in line with the city’s reforestation efforts. Apart from Mondays, the park is open every day from 5.30 am to 9.30 pm, making it very accessible to residents with different daily routines.

A space reclaimed by local residents

Parque Imán is a pleasant and very modern park that caters to all groups of citizens: Ramps make it accessible to wheelchair users and people pushing prams, and the skating area is ideal for youths to hang out. The climbing wall with a playground beside it is a perfect family destination, and the countless benches and picnic tables invite everyone to take a break and enjoy the park. The adjacent asphalt plant, which is still in use, produces a faint smell of freshly paved streets, but other than that it does not disrupt the happy bustle in the park.

Francisco, a local resident who comes to the park in order to relax and walk his dog, commented that the park is very nice and clean. However, Mario, another local resident, complains that there is too much sun during the hot afternoon hours because the trees are not big enough yet to provide sufficient shade. He also says that some people are concerned about the soil quality of the park, since the soil around the asphalt plant is heavily polluted.

While there are certainly some aspects of the park that can still be improved, it is important to point out that Mexico City’s southern part now has a large-and growing-open space that has been reclaimed by the public. Instead of having a private developer build expensive homes, an accessible recreational space was created, which offers a welcome break from the hustle and bustle of the capital.

The participatory process, although not without flaws, is another big and important step forward in Mexico City’s regeneration attempts. Most importantly, the park is based on the citizen’s wishes and ideas, and public pressure will hopefully continue to help to minimize corruption in the further development of the park. So far, this strategy has worked out. At the same time, it is a signal to the outer districts of the city that they are not being neglected in terms of public investment. A further step towards SDG 11 and an important signal!

Originally published at https://www.urbanet.info on June 21, 2018.

Read more about SDG 11 in Mexico City:

SuSana Distancia: The Mexican Superhero Fighting the Spread of Coronavirus

#sdg11inmexicocity: Connecting the Outskirts to City Centre with Cable Cars