This is a republished article from Next City. I abridged it slightly.

Story by Poppy McPherson with reporting by Thurein Win | Photography by Steve Tickner | Originally published on July 18, 2016

Evicting the Residents of 555

Myanmar’s young democratic government wants to remake slum clearance, but “new” tactics look unsettlingly familiar.

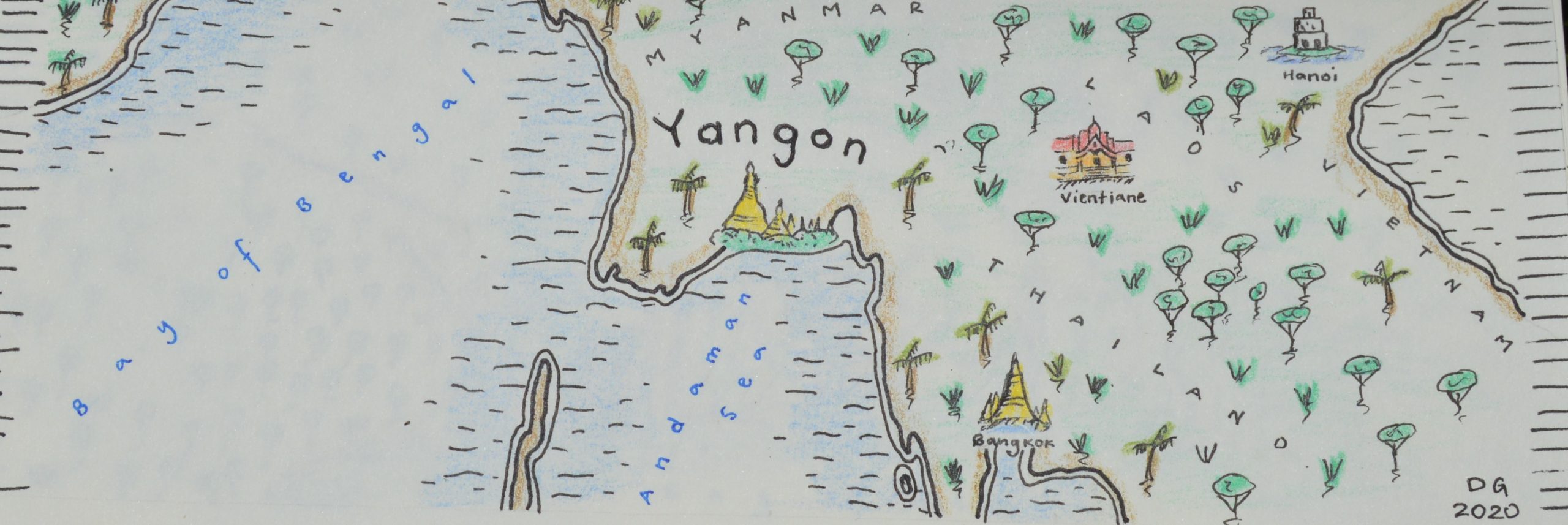

Once or twice a day during heavy rains, this village of huts built on the outskirts of Yangon, Myanmar’s biggest city, is inundated with 2 or 3 feet of dirty water. The downpours drag litter and sewage up and onto the doorsteps of the hundreds of people who live there. Waterborne diseases breed in the filthy black water. The residents call this place 555, after a cigarette brand produced in a nearby factory.

But, officially, the village doesn’t exist.

The people who live here are squatters. While some have lived on the floodplain for years, local officials refuse to grant them identity documents. Because of this, their children are barred from enrolling in public schools. Many of the families are survivors of Cyclone Nargis, a deadly megastorm that swept across the country in 2008. “We lost everything except our bodies,” says Mya Lwin, 38, who lived in the Irrawaddy Delta region. “We had no money to start life again there.”

Like many others, he moved to Yangon to look for work in the sprawling shantytowns that have grown up on the outskirts of the city. The suburbs are centers of industries that have begun to boom since Myanmar opened to the world in 2011. Factories cordoned off behind iron gates produce everything from salt to garments. But with a new government in power since April, the 555 residents are among hundreds of thousands of informal settlers facing an uncertain future as displacement looms on the horizon again.

A Well-Intentioned Mistake?

On the face of it, the policy sounds like a good one. Or, at least, a good-intentioned one. According to the government, it was dreamt up after Nobel Prize winner Aung San Suu Kyi and UNHCR ambassador Angelina Jolie visited Yangon’s sprawling slums together in 2015. These people live in abysmal conditions: Sense may dictate they should be picked up and moved somewhere else, somewhere better.

In May, Myanmar’s new government, led by Suu Kyi’s National League for Democracy, which won a landslide election in November, suddenly announced grandiose plans to move Yangon’s hundreds of thousands of squatters off the land they have lived on, in some cases for decades. Those found to be legitimately landless would be moved to “rehabilitation camps,” Yangon Chief Minister Phyo Min Thein said, while so-called “anarchical squatters” and “professional squatters,” those renting out land to sub-tenants, would be evicted for good.

Squatters have no legal rights in Myanmar. While international standards devised by institutions like the World Bank guarantee compensation for not only legal residents but also squatters in the case of eviction, Myanmar does not enforce them.

“It is frighteningly common for people in Myanmar to lack formal land titles and be evicted on that basis,” says Vani Sathisan, a legal adviser with the International Commission of Jurists, in an email. “Disputes over land ownership and use are a major source of social and economic tension.”

“Under the past 50 years of military rule, land has been frequently confiscated from farmers with little or no compensation and illegally transferred to cronies and private companies of the former junta,” she adds. “It does not bode well for the current government to repeat the old mistakes of the former administration, not have meaningful consultation and informed participation of individuals and groups, and move people to ‘rehabilitation camps.’”

A Surprise Eviction

The new plans came as a surprise to people living in 555 and the other informal settlements in Hlaing Tharyar Township, Yangon’s most densely populated area. Even as authorities began their headcount in June, some residents were unaware. Others had only heard rumors. “I heard they are doing a census,” says one girl who looks to be in her teens, her long black hair tied up in a ponytail. “I heard the people on the beach, they were talking about it.”

Nay Shwe, a stocky, animated man in his 50s who has lived in a small hut near the water for two decades, knew the details and was angry. “I want to plead with my government that they should recognize that some of the people have been living here for almost 20 years,” he says, holding a cheroot, or Burmese cigar, between his fingers. “They should recognize this place as a village.”

Nay Shwe moved to Hlaing Tharyar in 1996 as a construction worker employed to build the upmarket Pun Hlaing Golf Course — a gleaming image of wealth right next door to the slums. He rifled through a plastic wallet to pull out a crumpled, yellowed letter granting permission for himself and several other laborers to live near the grounds. At the time, there was little more than vacant scrubland. “We have endured hardships since that time until now,” he says. “We had to pump much sand from the river to live here.”

Subsequent years brought tussles over the land. In 2012, he spent six months in prison for organizing protests against a planned forced eviction that was eventually suspended. The latest announcement was unexpected. “We got the news from the BBC about the government’s plan,” he says.

The details are desperately vague. Lawmaker Aye Bo, who represents Hlaing Tharyar Township in Parliament, says that he has “no idea” about the future housing for the squatters.

“Generally, we [the administration] have the attitude towards them that they are humans and citizens of our country, they should have every right and dignity,” he says when reached by phone. “Up to now, I have no idea where they will be moved to. But we will arrange the better situation.”

He confirmed that the idea had been dreamt up after Suu Kyi and Angelina Jolie had visited the area in 2015. “I think that was the beginning of the idea of helping them,” he says. “We will try not to make them squat somewhere again. They are all humans like us.”

Local officials were equally unsure about the details.

“They are still not sure where they will be moved to,” says Nyunt Win, a soft-faced NLD chairperson for Hlaing Tharyar. A T-shirt printed with the image of independence leader Aung San, Suu Kyi’s father, was tucked into his longyi. “We were told that the real squatters here must leave, according to the rules in this area. If they don’t have a job, they will be given a job. We just heard that. They will not be moved somewhere far away.”

Asked where they would move, what jobs they would be given, and what sort of houses, he gave variations on the responses “I’m not sure” and “I think they have some plans.”

Nyunt Win and his colleague Hla Thay share the incoming government’s vitriol toward “fake squatters” who they claim cause most of the problems in the community. “So the first kind [of squatters] are real, landless squatters,” explains Nyunt Win. “The second ones are making business here. The third ones rent to the other squatters and some are just like anarchistic squatters.”

Walking down a path past a cluster of ducks that quacked as they tucked into bags of abandoned rice, Hla Htay points to shelters indistinguishable from their neighbors: “These houses here are the real squatters,” he says.

The others, so-called professional squatters, claim ownership to land that is not theirs, and illegally sublet it to poor newcomers, he says. “Some of the people here are giving some money to some officials, so they never considered solving the problem of squatters here.”

It didn’t take long to find a resident locked in a dispute with one of the informal landlords. Ei Shel, 30, leaned out of an empty window in her wooden shelter and stared with big, round eyes. The hut she shares with her husband and children stands on brackish water afloat with crushed tin cans and other garbage.

She says she paid someone about $50 to move in. “Now he is saying that he didn’t sell to us, he let us live here for free,” she says, as two babies paw at her chest.

They have no documents, or proof of payment, to stop him kicking them out, which she says he wants to do. Her husband earns about $8 a day as a construction worker, and they cannot afford to move. If they were forced to, she says she has no idea where they would go.

While encounters like this are common, urban experts working in the area say that professional squatters make up a small minority of the population.

According to Eben Forbes, a Yangon-based housing specialist who has worked for UN-Habitat in Myanmar, they have often been community leaders, formerly known as Heads of 100 Households. “The Heads of 100 Households are known to act as informal landlords or real estate agents in squatter areas, and do so with the cooperation of ward officials,” he says. “But the real point is that the great majority of squatters are simply poor people who have made a rational choice to spend less money on housing, and more money on feeding their families.”

In recent years, the cost of housing in Yangon has skyrocketed. After the country began to open, rent soared by as much as triple. With land at a premium, forced displacement followed. Thousands were forced out of their homes in Dagon Seikkan Township, as authorities tore down homes to make way for “low-cost housing.” Starting at $20,000, this was unattainable for then residents as well as many others living in poverty who, according to UN-Habitat, make up at least 40 percent of the city’s population. Since then, evicted residents have simply sought out other areas to settle in what Forbes called a “cycle of squatting and eviction.”

“It is the start of a gentrification process,” he says. “The few former residents who were able to squat nearby could continue their livelihoods mostly uninterrupted, but those who were forced to flee to the suburbs now have to endure long commutes to keep their former jobs or else have to start from scratch in the new location. In general, the trend is a bad one for keeping a socioeconomically diverse population within the city. The central business district employs as many unskilled and low-skilled workers as highly educated professionals. Both groups should have equal access to the city center, but access is rapidly diminishing for low-income people.”

“Right to the City”

Yangon is at an unusual turning point. The new government has a unique opportunity to avoid mistakes made by its regional neighbors.

In the five years since democratic reforms swept the nation, its economy has grown significantly as have its cities, keeping with trends seen across Asia. While only one-third of the country’s population of 54 million live in urban areas today, that share is rapidly increasing as rural migrants continue to seek the opportunities that sent Nay Shwe to Hlaing Tharyar two decades ago. In Yangon, construction industry estimates pinpoint the influx to be around 330,000 newcomers each year. Projections from the World Resources Institute anticipate that by 2030, 48 percent of the country’s residents will live in cities that are certain to be even less affordable and denser than they are today.

“No city in Asia has ever been able to tackle the problem by eviction,” says Michael Slingsby, a former consultant with UN-Habitat, in an interview in Yangon. “You just push people from place to place. If you look at who is coming, it is people in the 15- to 24-to-29-year age group,” he says. “They are young people who have come to look for work. And the government needs those people. Because they’re the people who provide cheap labor. That’s the basis of the economy at the moment. So trying to push these people away is likely to have a negative effect on the economy. At this stage of the economy opening up, we’re looking at a lot of low-skill, low-paid jobs and there are the people who provide it.”

“When we describe the slums we always describe the negative things. We never look at the positive things. These people are great survivors. … Somehow they manage to survive.”

Slingsby has worked in cities across the region, including Phnom Penh, the capital of Cambodia, which confronted the kind of rapid growth and modernization in the early 2000s that Yangon is experiencing now.

“[Phnom Penh] has faced the same problem of land speculation and so on that potentially we are facing here, so there are lessons to learn from Phnom Penh [that] are relevant to the development of Yangon,” says Slingsby.

Yangon authorities could look instead to places like Bangkok, the capital of neighboring Thailand. That city is packed with single rented rooms occupied by people who come to work in department stores and offices and want affordable, decent places to live. “There are hundreds of these all over Bangkok that are done on a purely commercial basis,” says Slingsby. “No government involved.”

Offering free housing isn’t necessarily a solution. “I’ve yet to find a country that gives land for free, that gives housing for free or very highly subsidized. … You quickly run out of money and you end up with a lot of disillusioned people who thought they were going to get cheap or free housing and then they don’t,” says Slingsby. “The trick is to allow people to get loans [that] they can afford.”

In more than 250 cities across Thailand, community organizations using government funding have provided loans and technical assistance for groups of people to be able to improve their housing conditions. “The big advantage of group loans is that people form housing societies and cannot sell to outsiders,” says Slingsby. “If they want to move away they have to sell the house back to the society, have to find another poor person to sell to. If you do it on an individual basis there’s a chance of speculation. A chance of gentrification. In Thailand, that’s been avoided.”

One organization in Yangon, named Women for the World, is doing just that. The organization groups people into savings collectives, which then pool their resources and decide how to spend them. Often, housing comes first. “There’s a very strong tradition of people saving together, working together for the improvement of their community,” says Slingsby. “We assume people are there waiting for government to do something.”

He recounted a recent conversation he had at a housing workshop. “One man stood up and said, ‘If I look at the budget, it’ll take another 15 years to build a new road in our township.’ We saved and we built it in two years.’ So you’ve got this spirit of people wanting to improve their homes and that’s something that needs to be developed.”

Policies that treat informal settlers as objects to be shuffled around fail to treat them as agents of their own destiny.

“When we describe the slums we always describe the negative things,” says Slingsby. “We never look at the positive things. These people are great survivors. … Somehow they manage to survive. Somehow a lot of them send their children to school and even to university. Who built the houses? The people built houses themselves.”

When their kids were turned away from the official schools, the 555 residents simply built their own. They recruited their own volunteer teachers. On a recent morning, a group of village elders, all men, stood outside and admired their handiwork. Like most of the structures in the area, the single-story school is propped up on wooden stilts to protect it from the rising water.

“So flooding is a problem here, but we can build a concrete road, so flooding for two or three hours is OK for us,” says Hla Htay.

555 might not exist, officially, and it might not be good land, but it is home.

“We prefer living here because it is the nearest place to our work, to the factories, so here we can build everything by ourselves,” he says. “We can build our houses. If we need to move somewhere provided by the government it will be expensive. … It will be a lot of rules.”