Participatory government in the time of COVID-19: in defense of the new normal

Written by Kyle Dontoh. Kyle is a board member of Open New York, a non-profit pro-housing activist organization based in New York City.

The COVID-19 pandemic has turned people’s lives upside-down across the world, no more so than in New York City, which in the spring months was the scene of one of the world’s worst outbreaks of the virus. While the city has begun a hesitant and uncertain re-opening (as I write this, public schools have just been closed back down), an uncharacteristic quiet, a discomforting stillness, still often prevails in most parts of what we once called “the city that never sleeps”.

The public hearing process has of course been no exception, large indoor gatherings of people (loudly) expressing their opinions perhaps representing the platonic ideal of a super-spreader event. This has not of course meant a total stop to the process; the work of government is, if anything, only more essential in times of crisis. What it has portended, though, is a shift from in-person meetings to faces-in-boxes of the Zoom (or other video-conferencing platforms) meetings with which most of us have, by now, probably become intimately familiar.

This change, while inconvertibly necessary, has raised the ire of a certain vocal segment of the public, who maintain the position that genuine participation, a meaningful exchange of views, cannot possibly come about through virtual meetings, “stage-managed” by their organizers to produce their desired result. Yet this criticism is misplaced. This shift has, by eliminating the factor of distance and significantly reducing the time burden, helped close one of the major gaps to participation in public hearings and planning sessions and offers the promise of a more inclusive model of participatory governance.

The “old normal”

The organization to which I belong, Open New York, advocates for the creation of more homes of all kinds, both affordable (subsidized) and market-rate (unsubsidized) in order to address the housing crisis which New York City and its metropolitan region faces. As such, the bread and butter of our activism entails engagement, in support of increased residential development, in participatory processes at all levels of the project cycle—community boards, the planning department, the Landmarks and Preservation Commission, the City Council—making the case for our pro-housing perspective.

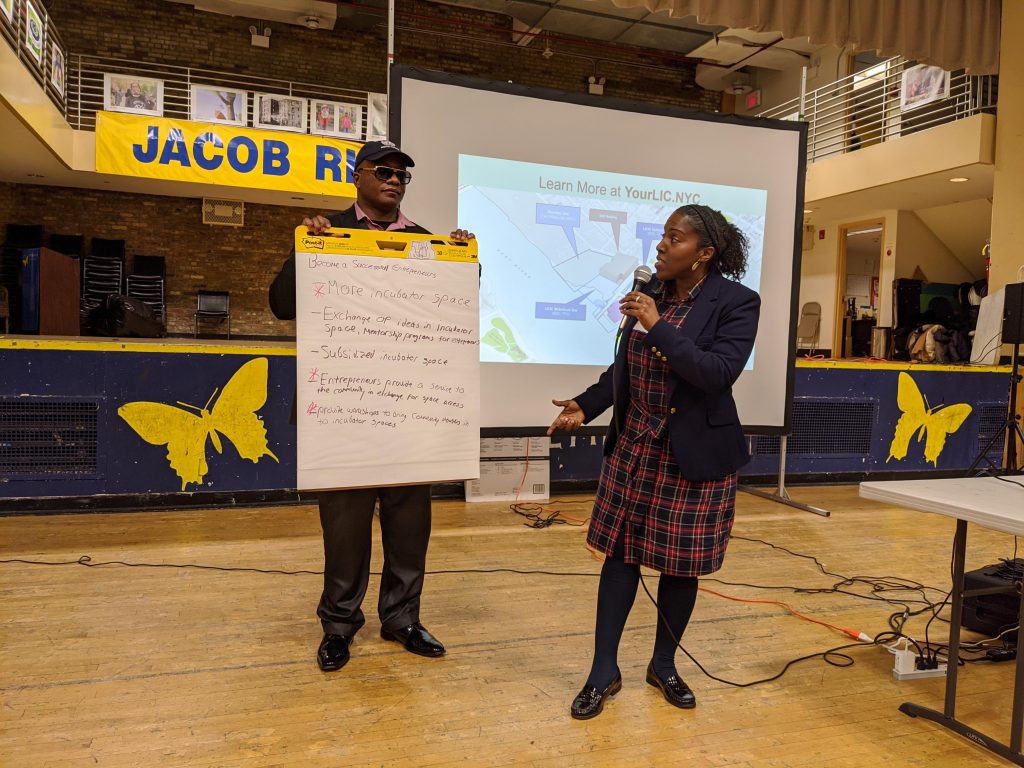

Having attended dozens of such meetings over the past few years, several trends have over time made themselves apparent. First and foremost is the question of scheduling. Many, if not most, hearings are held in the evenings—but more than a few are held in the late mornings or in the middle of the afternoon, at a time when few if any working people could possibly participate. As a graduate student for the past two years, I found myself with a slightly more flexible schedule where I could attend some of these meetings, and the disparity was obvious; aside from those with a direct interest in the project or proposal up for discussion (developers, construction unions, preservation organizations, councilmembers or their representatives, and the like), the crowds at such mid-day meetings predictably skew older.

Even those meetings scheduled at more reasonable hours are difficult for those facing the ordinary constraints of working or family life. As my colleague Casey Berkovitz has described, such meetings can drag on far beyond their scheduled end time, stretching late into the night, as moderators struggle to keep impassioned and aggrieved speakers to their allotted speaking time. Frequently, particularly in community board meetings, the members who are notionally serving as impartial facilitators make little or no effort to conceal their own opinions, and freely let those who share their point of view expound on their claims while avoiding calling on those whom they suspect to hold a dissenting perspective. For young parents, service workers, or even people just hoping to get home at an hour where they still have time to make dinner or do the laundry, the prospect of a public meeting stretching past midnight is hardly any more appealing than that of one at 2pm.

The impact of this burden is striking—not only are the people who attend such meetings likely to be older than the average New Yorker, but are also more likely to be whiter, wealthier, and homeowners. This is hardly limited to New York; a study in metropolitan Boston found that participants in community meetings were older and more likely to be white, male, own their homes, and long-term residents. It is however particularly egregious in a city where ethnic and racial minorities constitute 65% of the population, and 68% of people rent, rather than own, their homes.

New Yorkers, as is the case in most large cities in the United States, generally pride themselves on their progressive politics, openness towards social change, and, especially under the Trump administration, acceptance of newcomers. It is somewhat striking, then, that the public engagement process exhibits such a backward-looking bias towards those who can boast the deepest roots in a neighborhood; it is often the case that community hearings can resemble a competition for who can claim to have lived there for the greatest number of decades. The rhetorical gap between bemoaning “transients” from Ohio and those from Yemen, Guatemala, or Senegal is not particularly large.

The result of this skewed system is a baked-in resistance to change, and the incentivization of oppositional rather than supportive stances. With respect to housing, it favors the voices of those for whom the status quo has been beneficial, as opposed to those who have been most affected by the housing crisis—who are, conversely, more likely to be younger, poorer, non-white, immigrants, and renters. Political leaders, as a result, look more favorably upon building new housing in poorer areas where residents are less likely to be politically engaged, rather than risk raising the ire of people in whiter, wealthier neighborhoods, even when they’re closer to jobs, transit, and private development is more likely to be able to support affordable housing.

As the Boston study showed, the voices promoted by the process are clearly non-representative. In Cambridge, where 80% of voters backed a pro-affordable housing ballot measure, just 40% of speakers at public hearings expressed support for it. Organizing for change, in the face of such structural hurdles, required disrupting the existing process and creating something more egalitarian—and help came in a rather unexpected form.

Little boxes, big changes

In the initial first months of the COVID-19 pandemic, public meetings, like everything else, where shut down “for the duration”, the idea of a “pause” merely lasting a few weeks or months doing little to inspire innovation, it being assumed that things would, before long, simply snap back to normal. When it became clear that things would not be so simple, however, city officials began to adapt the new ways we’d found to work and meet for the world of public participation, and the process slowly began to restart virtually.

The impact of the shift was almost immediately apparent. Attendance at hearings on projects that had, before COVID, attracted between 50 to 100 people now drew in 200 to 300. One particularly contentious meeting regarding a temporary homeless shelter on the Upper West Side had over 1,100 participants—yet was kept to a comparatively compact 2-½ hours in length. With the constraints of geography removed, people could now listen in at their leisure from their home, the park, or even outside the city altogether, a non-trivial consideration in light of the fact that 300,000 people have left the city since the start of the pandemic. Essential workers on shift jobs could follow in on their phones, or on the bus or subway ride home. With this one change, the barriers to participation had fallen to a far greater degree than ever thought possible.

It was not long before the complaints began. Community board members and the aggrieved public alike complained of “limitations on necessary debate”, “technical difficulties”, and the inability of older community to members to participate. Yet the most ferocious criticisms revolved around the idea that people, expected to stick to strict, timer-enforced time limits and unable to interject at their pleasure, were in some way being censored, now that their God-granted right to jeer and harangue anyone who disagreed with them had been limited.

Without a doubt, there are legitimate concerns about older and low-income New Yorkers, lacking either reliable internet connections or tech savvy (or both), whose ability to participate. Some have suggested remedial measures, like airing meetings on public access television, or enabling members of the public to call-in via telephone, worthwhile steps worth considering seriously. Yet it is abundantly clear that the virtual shift has done much to broaden the range of public participation, rather than narrow it, and we should not lose sight of this. Certainly, the work of government should not be brought to a halt, as some have dared to suggest, until in-person meetings can be held again, a proposal that should be rejected for the stalling tactic it so clearly is.

“Augmented reality”: the future of participatory governance

Thankfully, the light at the end of the tunnel of this pandemic is nearly in sight. Yet rather than bring these online meetings to an abrupt end once we are able to declare ourselves “finished” with the coronavirus, it is worth contemplating the nature of the gains it has brought to the public participation process. It is not as if the problems it has helped address were caused by COVID-19; they were clearly independent of it. As such, reverting to an entirely in-person format would simply reduplicate the flaws of the past without drawing real, enduring lessons from the experience of the past few months.

Skeptics of the virtual format too have their merits, and it is highly unlikely that an exclusively online format will persist for much longer than is strictly necessary. Yet there is no need for an either-or approach: it is more than possible to integrate the two, and capture the best of both formats. Livestreaming hearings, and enabling people to call in remotely, would maintain the inclusive nature of online meetings, while allowing those who wished to be physically present. The simple tools used to maintain the orderly and time-efficient proceeding of hearings and public comment sessions—timers and microphone cut-offs—are easily adaptable to in-person formats.

The past few months have presented us all with a level of adversity precious few of us had ever before faced, yet we have proven ourselves capable to rising to the challenge of the adapting to such unimagined circumstances. The lessons we have learnt in that time should not be dismissed as only having temporary significance, but a lasting legacy that, if heeded, would permanently improve how we engage our communities and manage our cities.

Thank you, Kyle!

You might also like this article: