East Birmingham is a deprived area of the post-industrial city, with over 60 % of people living in the most deprived percentile. Improving living conditions and access to green space is a priority for Birmingham City Council, for example by providing four new pocket parks. However, when the Council had to declare bankruptcy just after starting this project, it looked like they couldn’t keep their promise. Luckily, UK-based practice Intervention Architecture and the National Trust with its Urban Places Programme pulled through and managed to deliver the pocket park in Firs & Bromford on a tight timeline and low budget. It is a particularly good example for how to provide value and environmental justice in inner-city communities.

Improving access to nature in East Birmingham

Firs & Bromford in East Birmingham is an area that scores poorly on the city’s Environmental Justice Index. This means that residents have limited access to green space, are disproportionately affected by climate change, and face higher levels of deprivation and health inequalities.

Intervention Architecture, together with the National Trust and Birmingham City Council as well as the local community via the Open Door Community Foundation grassroots organisation, worked on changing this by improving access to nature, cultivating an interest in growing, and fostering a sense of ownership over green spaces. They identified four parks from the environmental justice mapping that were at risk of floods, urban heat islands, and health inequalities, with the goal of improving access to high-quality green space.

The Firs & Bromford pocket park is one of four sites co-designed and co-built with the local community in Birmingham. It transforms an underutilised patch of grass alongside a busy bus route into a vibrant pocket park. By celebrating local history and incorporating over 50 different colourful, edible, and low-maintenance plants that encourage biodiversity, it provides a space for socialising, relaxation, and nature connection.

Unusually, the National Trust – a heritage and nature conservation charity and membership organisation – supported an inner-city project with the aim of addressing unequal access to nature, beauty, and history in towns and cities. To be acknowledged by an organisation like the National Trust brings a lot of pride to the local community, as well as visibility. The UK’s Shared Prosperity Fund funded the project together with Birmingham City Council.

This pocket park in Ward-End, the second of the four projects, also aims to improve living conditions and access to green space in East Birmingham. Credit: Paul Miller

Creating a well-loved space with and for the community

Perhaps the most striking aspect of this project is the successful community participation. Marina Strotz, Associate Director of Intervention Architecture, says: “From the outset, we – as a collective with the National Trust and Birmingham City Council – wanted to make sure the project was a true co-design and co-build with the community that would use the park, and not just a design for them. There was a lack of trust with the council, which is why we focused on quickly building trust with the community.”

Intervention Architecture undertook the engagement, design, and delivery of the pocket park, while the Open Door Community Hub supported the community participation process with an asset-based approach that proved to be central to the project’s success and impact: focusing on chances and opportunities rather than what is missing. That included showcasing local history, such as the former horse racing course on the site, as well as the suffragette history in Firs & Bromford.

The site used to be an end point for horse races, which is reflected in some of the design. Credit: Paul Miller

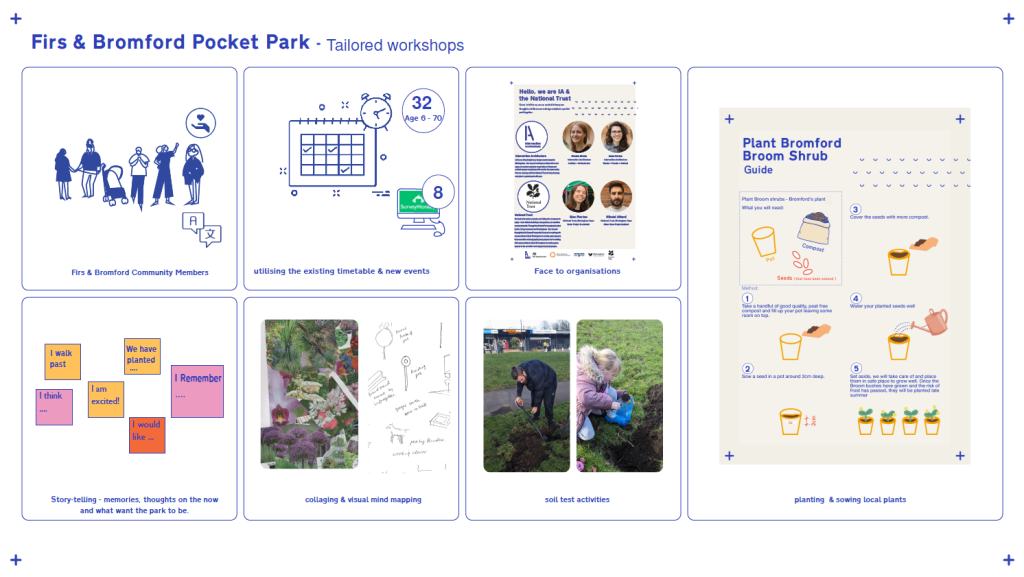

Marina and her colleagues engaged over 80 people in the design and co-building process: “We put a face to organisation members and offered different activities for the community like storytelling, collaging, and visual mind mapping to define a common vision.” In alignment with community hub hours, the programme offered participatory activities for all, including for those attending after-school sessions, men’s groups and planned drop-in sessions as well as online surveys.

Over 40 volunteers of diverse ages and nationalities came together over the course of several weeks and eight co-build days to bring their vision of a park design to live through:

- Painting

- Soil preparation

- Path and bench building

- Sign drawing

- Planting plants

- Sowing wildflower meadow seeds

- Planting local broom bush seeds that give Bromford its name

- Hard landscaping

“I remember the joy of the children planting the wildflower seeds. That was a fun day.”

Community member

At the end, the team organised a community handover so that volunteers are able to maintain the garden from now on. This included hands-on training from award-winning garden designers and a National Trust Head Gardener alongside a clear pictorial guide for maintenance. This includes signs throughout the park with tips and rules for looking after the greenery, as well as fun plant puns and nice messages.

Over 40 volunteers co-built the pocket park. Credit: Paul Miller

“Now, there are frequent gardening sessions, social events, and educational workshops, ensuring the parks remains a vibrant and well-loved space”, Marina reports. The team has been invited back and pride in the park evident both on-site and online through community Facebook page. A maintenance grant, provided through the project funding, supports Open Door in the park’s upkeep and stewardship.

Countering participation fatigue

One of the challenges that Intervention Architecture wanted to tackle heads-on was participation fatigue: “This is a community which is used to being asked to do questionnaires all the time, and they tend to get a bit of consultation fatigue”, Marina explains. But she has found that engaging the community through a rich timetable of events and specific days for co-building with a range of activities, it was possible to get everyone involved.

Different workshops, advertised through posters, and putting faces to the organisers from Intervention Architecture and the National Trust, helped to build trust and enable community participation. Credit: Intervention Architecture

A key concern was to make sure people could be open about their needs and feel safe. “A lot of people were thinking about the gathering spots they had back home, like big trees and seating to sit somewhere together and chat. We wanted to weave that through the design, so instead of ornamentals on one side and an allotment on the other side, it is all kind of a flow-through”, Marina says.

“People use the path on their way to the shops and school. Kids sit on the benches after school and people pick and use the herbs.”

Community member

Another challenge was the tight timeline: The project was appointed in September 2023 and due to be delivered in April 2024. During this time, Birmingham City Council had to declare bankruptcy, but the pocket park was still able to go ahead thanks to its outside funding and the dedication of both the community and the architect team.

“And obviously, there are always logistical points that in hindsight, we would have done differently. For example, we ended up with a lot of soil turf and ended up asking people in the neighbourhood if they wanted to take it home. We also created a bank out of the turf to have a seat.” But overall, working with all stakeholders and being clear in terms of what is possible and what is not, Intervention Architecture was able to make sure that everyone was happy with the overall quality of the park.

Places to gather were a priority for the community. Credit: Paul Miller

“We decided what our community wanted”

Now, one year after the park was handed to the community, it has flourished with minimal losses. It was shortlisted for a Pineapple Award, representing West Midlands. The project has been featured in RIBAJ and Marina Strotz was celebrated as a Rising Star in 2024 for integrating nature into the built environment. Delegates from neighbouring community groups and the Netherlands have visited to learn from the project’s co-design model for similar initiatives.

“We thought that there was going to be a lot of graffiti, but no – it’s flourishing. The community really sort of ran with it and has been fantastic. They have days where they look after the park. But even if they didn’t do anything, I think the park would still look great, a bit wild. We have had hardly any losses, and it’s fully established now”, Marina says.

Instead of graffiti, community members have left messages on these signs. Credit: Paul Miller

When asked for recommendations for other landscape architects, Marina says: “Just making sure that we weren’t restricting ourselves on ambition, even though we had a really tight budget, was key. We made that stretch as far as it could, which meant that we had to do a lot of the physical things ourselves, as well as making sure that all our insurances were aligned with the client insurances, that all those Terms and Conditions were in place. You know, there is a lot of trust going into doing work with the community and we really wanted to make sure that that aspect was never compromised: Even with a small budget and tight timeframe, just not letting the ambition and the main project goals ever fall was really key.”

This project shows the importance of a community’s involvement in designing and later caring for the park to genuinely embed social value and make environmental justice a reality. The team managed to engage people of all ages and backgrounds.

“Instead of other people deciding what our community wanted, we decided.”

Community member