What if a river could speak? Would it cry for help, or would it share memories of a wilder and freer past?

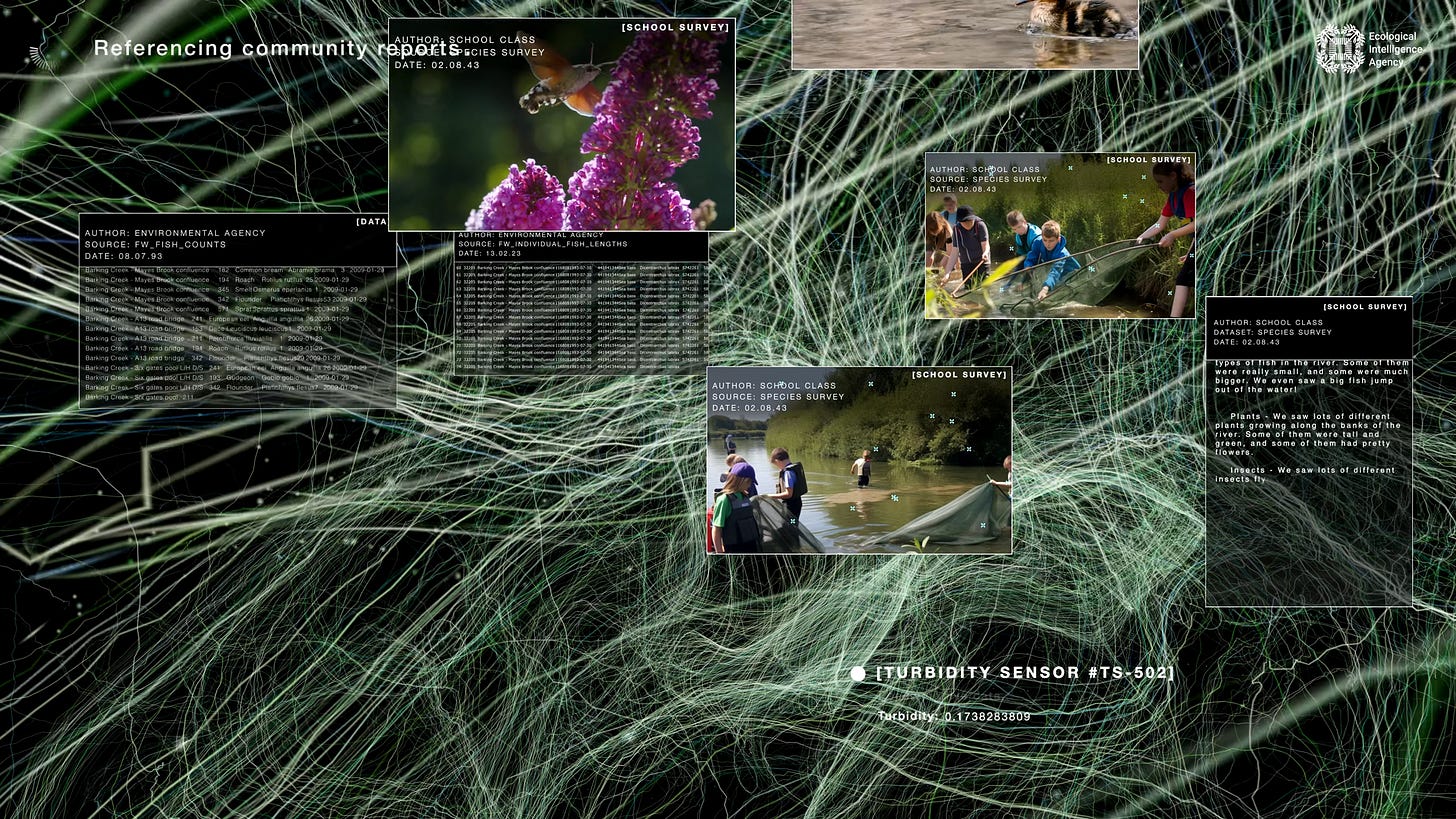

For Jon Ardern of the design agency Superflux, this is not a rhetorical question. “We have a lot of data, raw data, that tell us how bad [river pollution] is, but they don’t lead to change”, he says. His team is using storytelling and AI-generated poetics to help us listen differently – and feel differently – about rivers like the Roding in Essex.

Using a model built from scientific data, government reports, and community observations, the River Roding “speaks” in lyrical, emotional language in the agency’s exhibit at the Design Museums More than Human show. The model voices the river’s pain about sewage overflows, concrete constraints, and destructive flooding in ways meant to stir empathy, not just concern.

This approach to augmenting the data is key, Jon says, to understand how people might play an active role in saving their river.

Concrete, sewage, and rising waters

The River Roding, like most UK rivers, has been straightened and strangled. Where it once meandered, it now rushes through a narrow concrete corridor between Stansted and meeting the Thames in London. There are no spaces for reeds and no nooks for wildlife to hide in. Heavy rainfall increases flood risk – and in summer, sewage infrastructure issues can leave the river smelling bad.

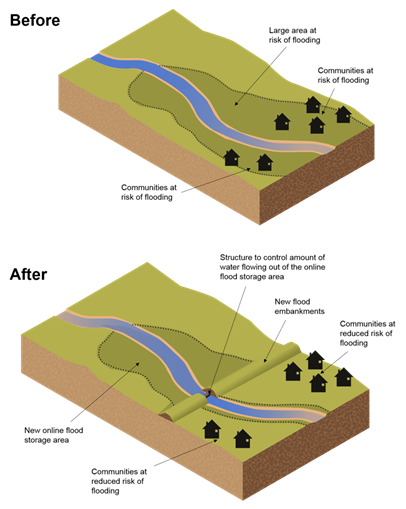

According to the UK’s Environment Agency, flood events on the River Roding have increased in frequency over the past 20 years, with the most serious flood occurring in autumn 2000. The frequency and intensity of such events will only increase, making it even more important to reduce the impact of flooding on the local area and the economic damage, financial stress, disruptions to daily life, and negative mental health impacts that come with it.

The River Roding Project – currently constructed by the Environment Agency for around £28 million – is set to reduce flooding by building temporary floodplains that will reduce the risk of flooding to around 1,500 properties, businesses, and infrastructure in Woodford and Ilford. A temporary reservoir will store water and drain it back into the river once high flows subside.

The river as a sacred being with rights

These efforts help, but they are only a part of the story. To truly help the River Roding, it is key to listen to it. Jon makes an important point about re-establishing an emotional connection with this important waterway. The River Roding Trust, a charity created by the barrister and environmental activist Paul Powlesland, takes a hands-on approach through picking up rubbish, planting trees, monitoring water quality and hosting events by the river. The charity also holds those companies that still release pollutants and sewage into the river to account, and pressures developers to design riverside housing that respects the river and supports the local ecosystem.

This is more than volunteering or activism: “The Roding is sacred, it is a being and it does have rights”, Paul famously told the Guardian in this great piece. He sees himself as a nature guardian with the mission to clean up this abused river, wanting to place it in the hearts of those who live beside it in East London and Essex.

Guardians upholding rights for nature

“The impact of this kind of work is hard to quantify”, Jon admits. Yet years after launching the project, people still contact him saying how much the project shaped their thinking. Some policymakers have adopted the idea of the river’s voice in workshops. This is slow work – but then, changes in worldview always are.

Paul Powlesland’s River Roding Trust focuses on direct action by reopening riverside paths, clearing waste, and organising clean-up days and tree-planting festivals to reconnect people with the river. “We need to open up this precious urban green space and revive the river,” he told The Guardian. “People don’t have the headspace to think about nature’s needs” – but at the same time, the area is lacking in nature and green spaces. By treating the Roding with more respect, it could become exactly the respected, looked-after park it deserves to be.

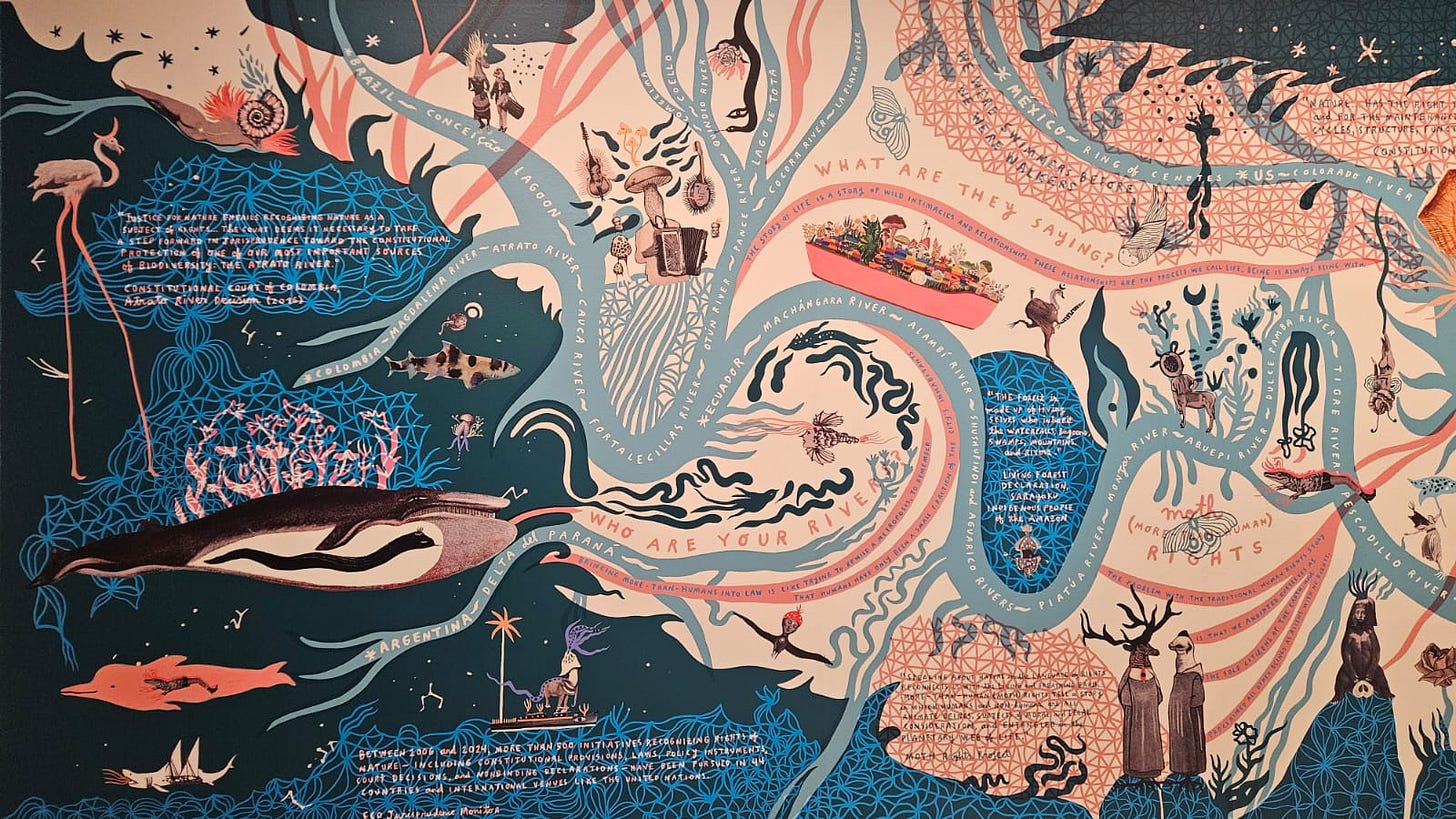

But barriers remain. Illegal sewage discharges continue to pollute the Roding, and accountability is difficult to enforce. Paul turns to the rights of nature movement as a solution – a growing international approach, led in many places by Indigenous activists. Already, rivers in Peru, New Zealand, and Canada have been declared as legal persons. While the UK lacks such frameworks, he believes citizens can assert rights of nature through hands-on care, advocacy, and community building, becoming river guardians before the law catches up. Paul explains his concept of nature guardianship:

“We don’t need to wait for someone else to change the law. You can connect with your river, form a relationship with it, and then act to uphold its rights.”

Remembering how to care

Listening to rivers isn’t just about improving water quality or creating better parks, it is also a shift in ethics that challenges the human-centred lens that has long shaped our legal, urban, and ecological systems. When we imagine rivers as beings with voices, we begin to reframe our relationships with the more-than-human world, making space for justice not only between people, but across species and ecosystems.

“We really need to hold people accountable for what is being done to those riverways, and we need to invest in changes”, Jon agrees. He is hoping for a shift in how we see these ecological resources. “There is a fundamental vision of rivers as an ecological service that is there for our use”. Most laws centre aim to limit damage so that exploitation can continue in a controlled way.

“We lost some of the connection in our current world view”, he says, emphasising that we need to begin to listen – not just to the data about rivers, but to their stories. Maybe then, we will remember how to care.

With thanks to the London Design Museum for inviting me to the press preview of “More than Human”, a thought-provoking exhibition that reimagines design as a collaboration with all living beings. Listening to rivers is one way we begin to shift from dominance to kinship.

Read how rivers can become more than places we protect, but also places we return to and swim in: