By Joshua Val Martin

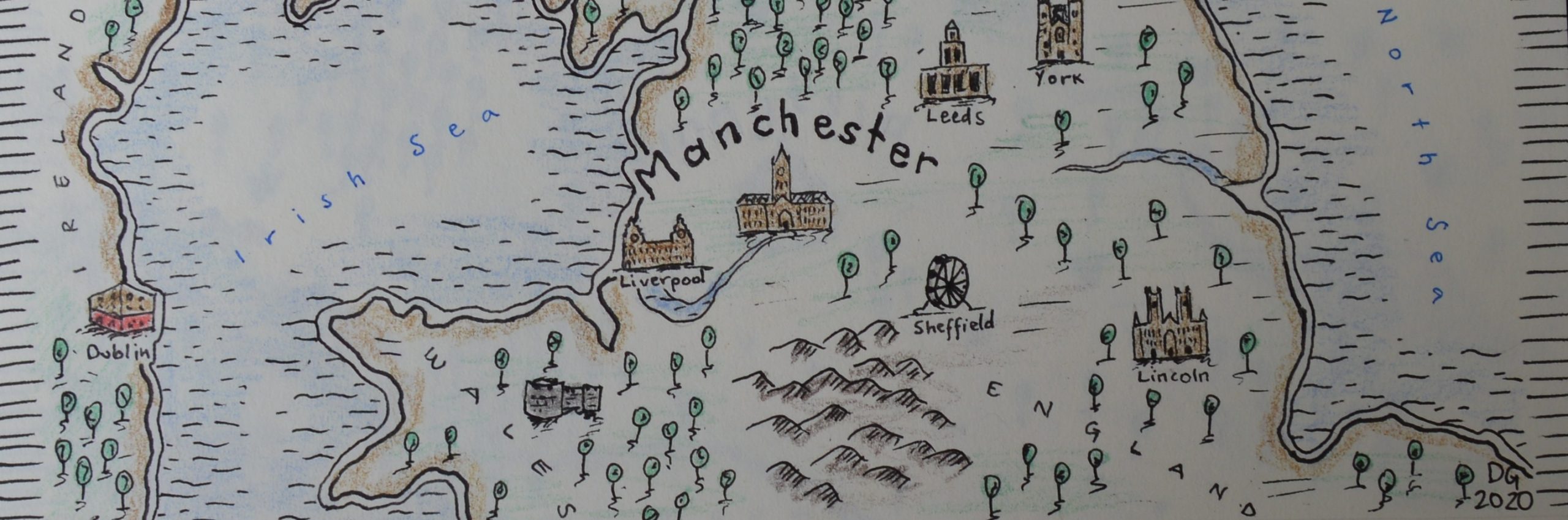

When I was asked to write about participation in the city, I did initially attempt to write a piece that included personal reflections and practical policy suggestions. But I work in the business of stories, in the walking tours that I run and in the plays that I write. I believe in the power of stories to inspire change. In my tours, I tell a number of stories that collate to create an idea of what Manchester is, in the minds of my guests. Manchester, like any city, is a very real and felt entity, but in reality Manchester is something that exists only in our cultural imaginations – it is a fiction that individuals collectively agree upon. Who does and doesn’t get to tell the stories that create ‘Manchester’ says a lot about the power politics of our urban spaces. And as I said, I believe stories are agents for change – and not necessarily for the better. In this post I am interested in how stories are used within the context of public/private space in Manchester, and the narratives of ‘regeneration’. Ultimately, I am interested in how these problematic narratives may be challenged through urban myth making being a more diverse, inclusive and more participatory exercise.

ACT 1.

The route that my tour takes, three times a week for nearly two years, hasn’t really changed. But certainly, the world around us is changing. The last two years have felt like the final moments before a theatrical interval: Britain voted to leave the European Union on the grounds of British sovereignty and an anti-immigration sentiment, and the nationalist tweeting TV-star Donald Trump was made leader of the western world and the world’s greatest military power. The world came to Manchester on the 22nd May 2017, at an Ariane Grande concert at the Manchester Arena, when a detonated nail bomb left 23 fatalities.

In the days following, I received around fifty messages from people around the world who’d been on my tour, who just wanted to let me know that they were thinking of me. It took me by surprise how much the event shook up friends and I alike, and so the messages were heartily appreciated. It was irrational for me to be at all upset, as I was not at the concert, nor had I known anyone there. I think it had such a profound effect on the people of Manchester, because it was felt to be an attack on ‘Manchester’. ‘Manchester’ is such a real thing in so many people’s minds. ‘Manchester’, as I found in the messages I received, is also something I have created in the minds of my walking tour guests through the collage of stories I tell on the walking tour. It is perhaps no surprise then, that in reaction to the attacks, newspapers and online media punned on the names of our football teams and referenced the heart symbol Marketing Manchester has used in recent years. There are a lot of arrogant quotes about Manchester that I open my tour with “Manchester has everything apart from a beach”, “What Manchester does today, the rest of the world does tomorrow”, “London might be the capital, but Manchester is the soul.” Look at the raw stats, and you’d find that Birmingham is the second city in terms of its population and GDP. And yet popular polls since the turn of the millennium unanimously cite Manchester as the country’s ‘second city’. I think it’s in these quotes you can begin to understand why: Manchester is a city of swaggering mythmakers.

An articulation of how this attack was felt as an attack on Manchester can arguably be seen in Tony Walsh being asked to read his poem “This Is The Place” at the vigil the day following the attack. The poem is an unapologetic celebration of Manchester. Many of the historic events he references in the poem, I also touch on in my tour – he reminds us that ‘this is the place’ where Marx met Engels and Rolls met Royce – where atomic theory was devised and later the atom split. Manchester writer Jeanette Winterson went on to comment that the poem “found words where there are no words”. It was not just poets and newspapers that felt the attack was one on Manchester- so did ordinary people. At the end of a subsequent vigil held in St Ann’s square, there was a spontaneous eruption of the Oasis song ‘Don’t Look Back in Anger’, arguably a Manchester anthem.

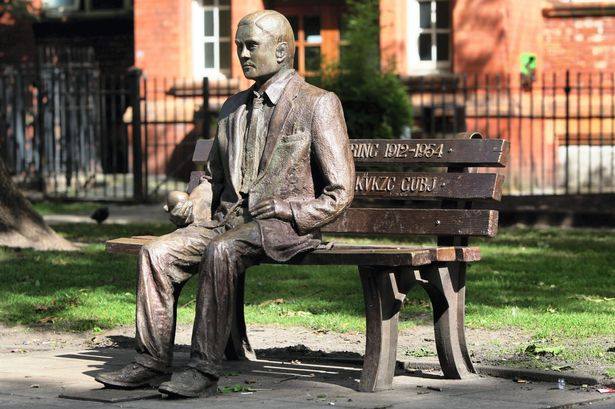

In a small park in Manchester’s gay village, there is a statue of Alan Turing. Alan is disappointed he doesn’t look like he had done. His face is too flat, and his suit too neat. But it says Alan Turing on the sign, so he knows he is Alan Turing. Last night’s ravers have smeared lipstick on his steel face, and yesterday’s revelers have left flowers in his hand – it had been the anniversary of his death. Alan thought about how much he’d changed since his death. When he died, the Manchester Guardian wrote little more than that he’d pioneered electronic calculating machines. Turing thought – if only during his lifetime, people had come to see him as a war hero, mathematical genius and gay icon. Alan wasn’t sure if any of this was completely true, but he thought, if people need that story to remind themselves who they are, then that’s the story they can have. There’s little he can do about it anyway now, he tittered, being a statue. All he can do is sit, and stare out at those occupying the small park.

ACT 2.

In Yuval Noah Harari’s popular science book ‘Sapiens’, he argues that homo sapiens – as far as we are aware – are the only beings capable of imagining things we have never smelt, touched or tasted. We create the fictions of religion, money, nation states and cities, because they allow cooperation on a scale inimitable by other creatures. Manchester exists in our imaginations, as something we collectively construct, in the myths we perpetuate. This sounds cynical but I do not intent to undermine the value of such myths – it gives us the utility to collectively grieve, support one another, work towards a higher goal – we can see beyond personal differences, and believe in the worth of ‘Manchester’

But we shouldn’t take such fictions of granted – just like when we are asked to unquestioningly have faith in religions and nation states. ‘Manchester’ may be a necessary gluing fiction, but is the process of making ‘Manchester’ a participatory one?

The ability to participate relies on the individual feeling empowered to do so. Therefore, I very quickly need to crassly paraphrase the flowery French philosophers I’ve misunderstood over the years, and think about the individual and the power politics of urban spaces.

Henri Lefebvre talks about passing the same landmarks daily (as I do on my tours), and how it is never the same (time, weather, people, sound, politic), and yet it is very much the same in its fixity. It is in the constant renegotiation between the physical environment and the body, that one is creating a ‘space’. Lefebvre also said that ‘space is a means of control, and hence of domination, of power.’ Michel Foucalt argues that ‘power’ lies in the boundaries that enable and constrain possibilities for action, and on people’s relative capabilities to know and shape these boundaries.

In this post, I’m not interested in the physicality of cities, but in how narratives within urban spaces create and shape boundaries, and act upon individuals. Stories I believe are used within cities as a method of symbolic power, silently and unconsciously acting on individuals. To understand how these stories enact power, we may be able to find ways in which Manchester myth making can be a more participatory process.

An obvious example of stories in the city, is that of my Walking Tour. I certainly exert a certain power when projecting narratives upon locations. The stories I tell include about the gay village, Alan Turing, rave culture, China Town, the Peterloo massacre and suffragettes… if you would ask a guest to describe Manchester after being on one of my tours, they’d probably tell you it’s liberal, queer and cosmopolitan. Of course in truth, this Manchester is not a reality, but an aspiration – the aspiration of the tour guide.

Because there is a lot of reality I conveniently forget to mention. It is almost criminal that the Manchester I create for the most part ignores the homelessness crisis, the problems of drug addiction, the poverty outside the parameters of the city centre – does anyone on a summer city-break really want to hear of the hardships of post-industrial life? I work on a tips basis, and so the Manchester I make is a vibrant exciting one – market forces are much more powerful than I am. We can see here that exciting stories can be used by those with power to cover less attractive narratives.

In a small park in Manchester’s gay village there is a statue of Alan Turing who sits and looks out, waiting for the world to wake up. As good as church bells, or birdsong, the park’s very own homeless tenant takes a seat beside Alan and sucks his morning fag, saying nothing more to Alan than, ‘Y’alright?’. Alan isn’t the the the the best with words, and even if he were, he’d not speak to the homeless man – not because he is homeless, but because Alan knows that Alan is a statue, and so can’t speak. And anyway Alan prefers puzzles – as spring had wriggled into summer, Alan had gone from imagining the homeless man as an ex-army hero struggling with memories of the middle east, to a manic depressive from Cambridge who’d run from the constraints of family life. Alan didn’t feel he’d found a solution to the puzzle that was the homeless man, but these television tropes were at least a small compensation for both of their inability to speak.

ACT 3.

In previous redrafts of this post, I have attempted to very broadly discuss the concept of power and narrative constructs in urban spaces. As genuinely fascinating as that would be, I unfortunately have not the time, breadth of reading nor mental capacity to qualify such work. So instead it is here that I’ll focus on an area of personal interest that is the so-called ‘regeneration’ or ‘gentrification’ of Manchester city centre.

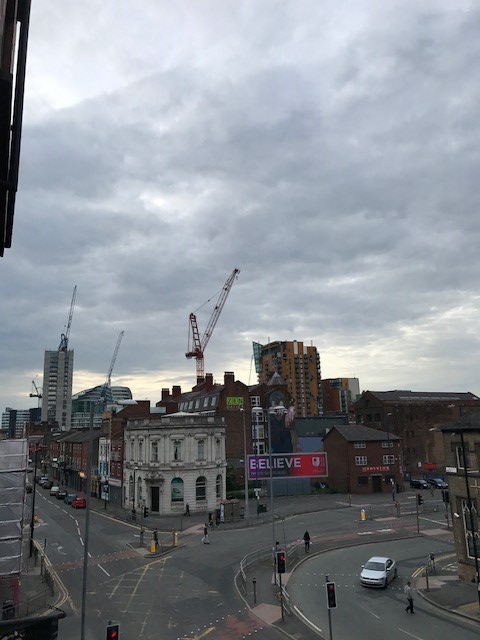

Notorious councilor Graham Stringer rather crassly believed that a ‘crane index’ (how many cranes you can see) is the measure of how well the city is doing. By this account, Manchester is doing very well indeed.

The neighborhood straddling Whitworth Street and Granby Row is characterised by the grandest of Manchester’s warehouses- many of these neoclassical palaces of industry were taken up as residential spaces by gay men in 1990s Manchester. Manchester’s gay culture was brought to global attention in Russell T Davis groundbreaking television series Queer As Folk (a piece of Manchester folklore in itself).

There’s a romance to the cheap spacious rooms overlooking both the city’s brutalist post-war pragmatism and the engineering innovation of the Victorians. As inner-city living became fashionable, landlords realised the money they were sitting on. In the last decade or so the inhabitants, some of them I’d call friends, have been asked to leave as the warehouses were refurbished and converted into higher end apartments. This movement of money and people is making our central spaces younger, more white, more straight and most worryingly, more private. The spot on the tour I once used to point at a Greek-revival facade and factory caracases, and tell of how they’d influenced the great Prussian architect Karl Friedrich Shinkel, I now say a coy hello to the landlord of said warehouse, who seems to take his fag break each day just as we pass his block (or perhaps he just takes a lot of fag breaks). I can no longer talk about his building because, like so many of the warehouses in the district, it is dressed in scaffolding, which drapes like theatre curtains waiting for the city’s next Act. Over the two years of touring, on my single route, I’ve seen the reopening of central library, a new tram line, the demolition of an art deco cinema, and the development of a disbanded theatre; the tour is like water down a river, treading the same route but in permanent renegotiation with the urban geography’s slow but sure evolution.

It is interesting to find how narratives play out amidst this symphony of gentrification (I say symphony, it is mostly pneumatic drills that make additional work for us tour guides).

All around the city, there are symbols that evoke the Mancunion narrative. Our bins, flowerboxes, bollard and buildings are adorned with the Worker Honey Bee – the symbol of the city and the Mancunian to say that – Us Mancs? We’re just like worker honey bees: working class, hardworking, and working all together. The statues that date from the 19th century depict influential and notable politically nonconformist men, such as Quaker scientist John Dalton, or the great social reformer Robert Peel. But who is it that is perpetuating these narratives, and what purpose do they serve?

The example which shows how I see how urban narratives playing out is in Tony Wilson Place:

The late Tony Wilson was a Mancunian and outspoken socialist, and the most prominent Hacienda / Factory records founder. His story is told in the film ‘Twenty Four Hour Party People’ (another piece of Manchester folklore). In the recently built and named ‘Tony Wilson Place’, there is a recently imported Soviet-built statue of Friedrich Engels, who was a long-term Manchester resident and together with Karl Marks, wrote the communist manifesto, partially in Manchester. Also in this Place, there is a cinema/theatre/art gallery named HOME, that has a reputation for more continental / alternative work.

And then, also in Tony Wilson Place, there is a sign reading “Private Property: CCTV in operation. Images are being recorded for the purpose of crime, prevention and public safety. No alcohol, canvassing, leafleting, skateboarding, rollerblading or commercial photography” – a crass articulation of our French friend’s theories of space as a means of control. Do not drink alcohol that we are not selling, do not promote ideas that may bother our paying public, do not make money out of the physical space we have created, do not engage in recreational activities that may bother the people who are spending money in the space. You are being watched – for public safety – and for their private gain.

In Tony Wilson Place the individual is reduced to a consumer of coffee, food, theatre and art. Tony Wilson and Friedrich Engels perform a façade of disaffection and resistance, symptomatic of what Jim Guigan calls ‘Cool Capitalism’. To badly paraphrase Joseph Schumpeter, capitalism makes a society that makes it possible for individuals to support the system and feel critical of it. How dare these financers build on a space, which had for a long time been used for trade union rallies, and appropriate the names of two politically charged minds, and then tell us we can’t canvass. Stories in Manchester, like the myths and legends of 19th century nation state building, are seductively stirring methods of control.

In a small park in Manchester’s gay village, a seated Alan Turing has seen it all before. One student at the sixth-form college copies homework from their ‘friend’, who watches on and smiles. Young men in suits run late yet still walk the longer way to work, because passing Alan and the pride flag brings them comfort. There’s an olive skinned dyke with a suitcase and backpack, gleaming at the red brick and grey skies, reading every signpost belonging to every monument in the park, before sitting beside Alan and waiting for a city walking tour. She’d not met a single person besides Alan, and yet she knew she was at home. Hello, she said to Alan in her refurbished English – this is my new home.

ACT 4.

The more educated, richer, whiter, straighter inhabitants of our central spaces can’t see the silent and sinister dispositioning effects, because the narratives of Engels, or the soon to be built Pankhurst statue outside the KPMG building, entitle a sense of alternative radicalism. But in truth, they encourage conformity. The stories constrain their possibilities for action, and render them unaware of their boundaries.

Still a young idealist, I believe that cities should be alters of cosmopolitanism and recognition. They offer the possibilities of greater co-operation and understanding – my favorite line of Tony Walsh’s poem at the vigil was “some are born here, some are drawn here, but we all call it home.” The more central spaces allow for the possibility for us to recognise our differences, the better possibility I believe we have for future global cooperation. My idealism is rooted in a line from Jean-Jaques Rousseau “Let the spectators become an entertainment to themselves; make them actors themselves; do it so that each sees and loves in the others so that all will be better united.”

There are many projects within Manchester that encourage greater narrative participation. Though I find ‘Manchester Day’ and it’s accompanying parade a little tokenistic, I thought the one-off event ‘What Is a City but the People’ commissioned by the Manchester International Festival, sublime. It was a catwalk in Piccadilly Gardens of Manchester individuals, with their stories projected on a screen. It was the embodiment of the Rousseau quote.

This has no legacy however, as fascinating as I found it. I find a more successful project in the long-term to be Cities of Hope. Internationally acclaimed graffiti artists took to Manchester’s hipster Northern Quarter area. The Northern Quarter was once a hub of artist studios and shops selling sex and second-hand clothes. This Cool does live on to an extent, but these days alongside yuppies and five pound pints. Cities of Hope, a not for profit social justice organisation, depicts issues such as child soldiers fighting in civil wars, lack of sustainability, immigration, homelessness, disadvantaged adult Mancunians, black gay men… Graffiti has been used in post-industrial cities à la New York / Berlin to give areas Cool, and so here Cities of Hope uses the language of Cool that the yuppies and artists understand to introduce narratives that perhaps they don’t understand. It is an intervention that uses the language of gentrification to challenge the unquestioned celebration of our city – a celebration that I am guilty of perpetuating in my tours – Cities of Hope begins to reclaim the city’s story. But only begins – it is still those with the gifts individually empowered who are able to share these stories. It is still not a fully participatory exercise.

In a small park in Manchester’s gay village, Alan thinks – Another vigil? We’ve had AIDS, Section 28, AIDS again, Orlando, Chechnya, The Manchester Bombing – that’s only naming a few- the cause is always worthy but he doesn’t see what the same soapboxes weeping onto the same grey grass can really do. And it always is the same faces: different fashions, different weather, different views, different heartaches, different moods, different plans, different shoes – but always the same weeping faces. Today it’s a vigil for one of those faces, who died before he should have. From the trees, these faces hang slips of paper with memories written on, about the face that they lost. Alan knows that no one will dare to remove the slips of paper from the trees, like the deathday flowers that still rest on his knees – It is only then Alan starts to see that these vigils aren’t about ‘doing’ anything, but about being there – strangers welled together by grief, lovers, accidents, illness, affairs (some current), booze – stories.

ACT 5.

Whilst I’d love to dig deeper into the many ways that stories around our cities create unfortunate juxtapositions, or harmonious coincidences (See Jonathan Schofield’s article fascinating article about a statue of Richard Cobden, and the Manchester Bombing here), I’m aware that this article has run much longer than others on this site and therefore I must speedily find conclusions – conclusions that I am lost of. How does one encourage participation in the creation of the myth of a city? How do I possibly get off my high and abstract horse, and reach into the gritty realities of making things happen? I think you have to be both relentless, and creative.

My friends have a theatre company called Might Heart Theatre, and they make their shows using stories that they collect from the people of Manchester, and they playfully use their words and bring their stories to life on stage. My friend Jez Dolan is an artist who worked with the central library archivist to find lost stories in the recorded voice archives, which he later used in a year-long arts project which included free exhibitions, performances and symposiums. The Royal Exchange Theatre regularly make free work, written and performed by local artists, performed to those who enter the public Royal Exchange space. The gay men’s choir The Sunday Boys perform in public spaces outside of the gay village, ensuring queer visibility. Manchester’s most exciting tour guide ‘Skyliner’ writes a blog about the more hidden aspects of the city, running a number of detailed more alternative tours, with gentrification and public spaces being an important theme. These tours are particularly designed to be inclusive of all visitors, including families and Mums. This is her blog: http://www.theskyliner.org/

The myth of Manchester should not just be made by those who consciously create, but a process that we all feel empowered to participate in. I believe the only real platform for participation of myth making is public space that is truly public. The idealisation of public space may seem like the abstract whimsy of Marxist urban geographers, but we only have to look at the space where I begin my tour, to see it as a real living process. I begin my tour in Sackville Gardens. ‘Gardens’ is a generous description; it’s a melancholy stretch of grass with a few trees, roughly the size of a 5-a-side football field, with paths that lead from the entrance gates, to a central statue of a seated Alan Turing. I would argue Manchester’s ‘Gay Village’ or ‘Gay Community’ (collectively understood fictions) are created and shaped partly within Sackville Gardens. The narratives that remind us of what the gay village is, specifically within this public space, can be found in many forms. There are self-funded memorials to local LGBT history; those who died of AIDS, and a wooden memorial to lost Trans live. Rallies for gay oppression in Chechnya, the attack at the gay nightclub Pulse in Orlando, and the LGBT response to the Manchester Bombings, have been held in this park. It is where vigils have been held for lost and dearly loved members of this ‘village’. The Gay Foundation charity, in their purple waistcoats, takes partial responsibility for keeping the gardens clean and tidy, and it also uses the park as a safe space to work with men who sell sex. There have been many outdoors Shakespeare plays, the annual Sparkle Trans celebration weekend, and a thrice-weekly free walking tour. It is where the homeless sleep alongside the students, the gays, the cruisers, the tourists, the still-out ravers and the yuppies. It is one of the few public central spaces in Manchester you can take a beer, smoke a spliff, play loud music, take ‘commercial’ photographs, skate, cycle (or move upon any other wheel of your choice) and no one will bat an eyelid. Sackville Gardens is an example of a public owning their space and creating their own myths and legends.

Humans are powered by stories. The way that we see and understand the world is shaped by the stories that we are told, whether via the front page of a newspaper, tacitly as we pass a statue, a piece of graffiti, or the collage of words and actions in a public space congealing like a TS Eliot poem. It is easy to take ideas such as The City for granted, and accept the story that we are told – Manchester: a city of scientific and industrial firsts, at the cutting edge of 19th century politics, which has risen like a phoenix from the ashes of post-industrialisation. We must encourage more creative and diverse participation in the questioning of such narratives, and formation of new ones, so that the Manchester that we make (or the Manchester that we aspire) is one that truly belongs to its people. We can only dream that the myths we create aspire to the final line of Tony Walsh’s version of Manchester: Choose Love.

In a small park in Manchester’s gay village, a seated Alan Turing resigns himself to listening, for what may be the fifth hundred time, to a tour guide telling tourists about Manchester. The guide always uses the same words, and the same jokes, and the same opening line ‘I say that four Manchester’s have existed’ – in fact Alan wasn’t sure if all of the stories he told were true, and he didn’t know if all the tourists believed that they were either –it’s like they’d all decided to agree there were more important things than reality, the statue of Alan Turing thought. The tour guide, as usual, shakes the hands of all of those waiting to do his tour, and attempts to warm them, charm them, ask just enough for the tour to feel personal. The tour guide shakes the hand of similarly young man, and the tour guide smiles. The tour guide stutters, ‘I say that four different Manchester’s have existed, and today-‘ looking at the young man once more, the tour guide, nervous, forgets his words. And so the tour guide must turn to the seated statue of Alan. He thinks of Alan’s story, the genius hero punished for loving. The tour guide smiles at Alan. Alan doesn’t smile back – because he’s a statue- but that’s okay. The tour guide says once more, with confidence – ‘I say that four Manchester’s have existed…’

See here for more information about Josh’s amazing free walking tours of Manchester. Thank you so much for your contribution!

Disclaimer: All pictures in this post were provided to me by Joshua Val Martin.