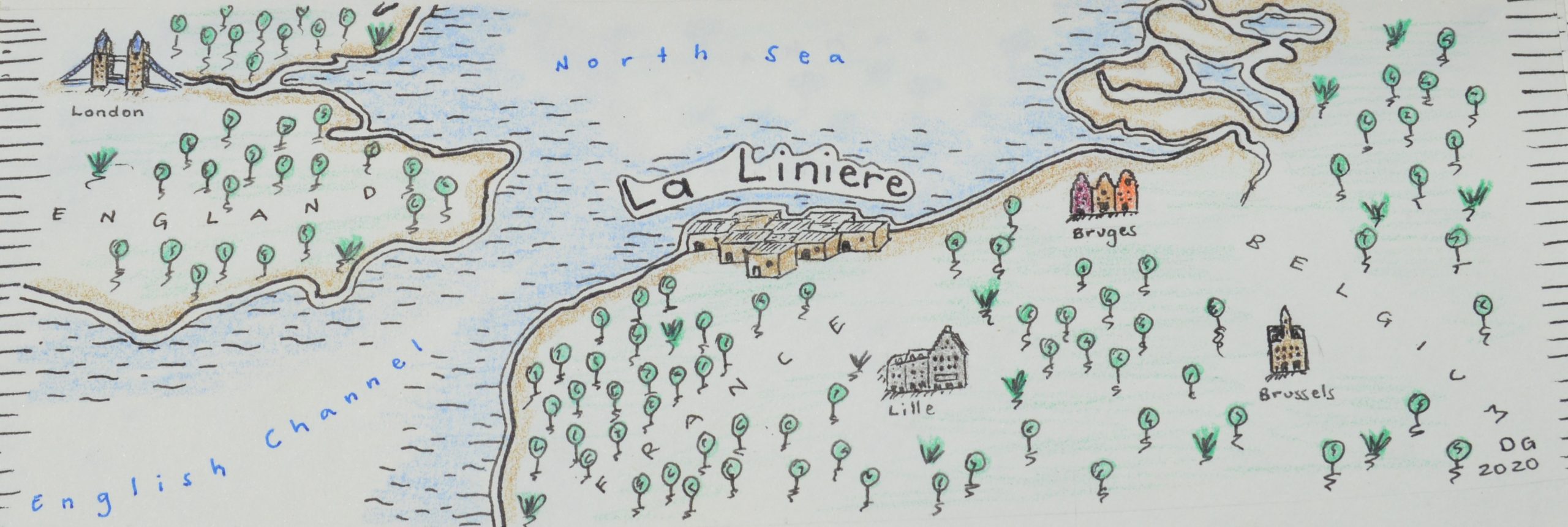

Voices from within a transit camp in Grande-Synthe, France

by Hanne Vrebos

26 May to 4 June, 1940:

The Miracle of Dunkirk: During a military operation 340 000 soldiers stranded in Dunkirk, surrounded by the German army, are evacuated to England after what Winston Churchill calls a colossal military disaster.

September 2016:

About 10 000 men, women and children are stranded again in Dunkirk and its surroundings, waiting for a rescue, after humanitarian disasters made them cross Europe. Unfortunately for them, their rescue doesn’t come in the form of ships send by the UK government to bring them to safety.

While they wait for a legal solution to cross, or more often, hide in lorries to make the crossing to a safer future, they stay in refugee camps, sometimes for weeks or months. The conditions are a harsh violation of human rights: children are left by themselves facing severe traumas, there is a lack of proper sanitation and water facilities, the residents are often detained, the living conditions are dangerous and there is limited provision of health care and education. Many organisations and volunteers do not close their eyes to these people left by themselves and set up initiatives and projects to improve the living conditions for these people.

As a volunteer and researcher I spent about 8 weeks in the refugee camps of Grande-Synthe. In my research, I looked at the voice of these camp residents. I was intrigued by how resident participation related to the physical environment takes place in a humanitarian camp.

When I arrive around 10 am, La Linière is quiet: some volunteers are going around with plastic bags collecting waste, others are setting up the food truck to start the morning food distribution: fruit salad, hummus, muhammara and bread, while other volunteers are repairing shelters. At the neighbouring tea tent, volunteers offer camp residents and volunteers a hot cup of tea and coffee. Some families with children are already awake, but most inhabitants – young men – are still asleep. People dressed in many layers of clothing walk back into the camp, a tired and sad look on their face: another failed attempt to cross the canal to the UK.

The canal between France and England forms the final obstacle for many refugees fleeing their country looking for a safer and better life in the UK. The refugees who strand in Northern France have a perception of England as a land of milk and honey. Faster asylum procedures, more liberal employment regulations, relatives and the possibility of a life in the shadow, as there is no obligation to carry ID, are the main reasons for this belief. However, the canal between France and England is a border that has proven hard to cross for many, and they remain stuck in one of the refugee camps in Calais or Grande Synthe.

The increased border regulations resulted in an exponential growth of residents in the camp in Grande-Synthe and inhumane living conditions in the beginning of 2016. The mayor of Grande-Synthe, Damien Carême, acknowledged this humanitarian emergency. As neither France nor Europe was providing any support, the mayor decided to set up a camp to humanitarian standards in collaboration with Doctors Without Borders (MSF) at the beginning of 2016. Following a humane approach, the residents of the old camp were informed in advance about the new camp and its open access by MSF. 1,300 people moved voluntary to La Linière in March 2016, where Utopia56, a French volunteer organisation, was assigned the camp coordination. In June, Afeji, a professional French welfare organisation, took over the coordination of the camp.

A walk through La Linière

The camp is located in an industrial area, 1.5 km away from the centre of Grande-Synthe, where the old camp was located. It is a fifteen minute walk away of a big supermarket. This location puts the camp and its residents out of sight of the city and leaves them with limited connections. The site is a long stretch of land, squeezed between a highway and railway that mark the borders of the camp. There are only two entrance points on the extremities. In combination with the long middle road and the openness of the shelter communities, this spatial organisation allows for easy control of the residents.

From the main road, a smaller road brings you to the entrance of the camp. While access is free, the organisations do keep an eye on who comes in and out and sometimes there are police controlling IDs. When entering the camp through the main entrance, you first pass by the most used public space: the cover charging area, with rows of electricity plugs, where residents can charge their phone batteries, children ride bikes and youth play basketball. Phones are crucial in the lives of the residents to stay connected with friends and family, to find their way during their journeys or to ensure their safety.

The camp has been set up through an integrated approach. There is a variety of spaces beyond the basic facilities: community kitchens, decentralised sanitary facilities, playgrounds, a tea and food square, schools, a hospital and a laundry. While these facilities are run by volunteers, residents are involved in the big kitchen and bakery and have set up small shops, along with other grassroots initiatives, throughout the camp. The community kitchens allow residents to cook their own meals safely instead of using gas stoves in their shelters. Separate and appropriate spaces for women, children and youth are answering to the needs of the most vulnerable residents of the camp.

During my time in the camp, the organisation Utopia56 was coordinating the camp, benefitting from strong relationships of trust with residents as a participatory process that constantly kept a finger on the pulse. At a welcome container and information point on a strategic place on site, Utopia kept track of the needs and desires of the residents. With tea and a cozy table, residents were welcomed to come and chat with the volunteers at this info center. The food truck and tea tent are other places where volunteers and camp residents get together. This welcome point was later closed by the new camp management agency, who established a formal reception point at the entrance gate.

Mapping

On Google Maps, there is no trace yet of the camp. Connectivity and information are very crucial in the lives of the camp residents. The organisation Mapfugees collaborated with camp residents to GPS track and map the camp, the surroundings and the most important connections. The intense collaboration with camp residents made that the map provided the information essential for them. Moreover, the training of participating residents and an open source mapping app allow the continuation of the mapping of the constantly changing physical environment.

Shelter

The shelters are small wooden constructions, grouped around public spaces. During the assessment and planning phase, participation was done through consultation and assessment. Following international standards, this resulted in household based uniform shelters, ignoring the high prevalence of single men. The shelters are about 9m² and house up to 5 people. They are thus not according to international standards of 3,5m² per person. Due to the small living space, the shelters quickly became incremental housing, more out of necessity than planned from the start. Volunteers, sometimes helped by the residents, would construct extensions in front of the shelters on request of the inhabitants. The additional room provides space for storage or a kitchen. Sometimes residents themselves would build extensions, and even connect neighbouring shelters to provide more private or semi-private space. The fast appropriation of shelters and surrounding space happens furthermore with stoves, furniture and make-shift boundaries, as an outside room extending the private shelter. Some rules are set up to control how residents extend their shelters to ensure fire safety.

Smugglers and crime

A newly arrived family. A young couple with a toddler, just learning how to walk. They first find shelter in the ‘buffer zone’, a series of white tents, while they wait for a wooden shelter to free up. A shelter frees up, its residents succeeded to make the crossing. We are quick to empty the shelter, which is far into the camp, and propose it to the young family. We show them the shelter, but they decide to stay in the tent, as the shelter is in the ‘smuggler zone’ and they don’t feel safe there. They will have to wait until a family crosses to find a space in the family area at the beginning of the camp.

The second half of the camp was assigned to single men and has less community facilities, as these are mostly situated at the beginning of the camp. This results in less activity and movement at this part. Missing what Jane Jacobs called the “eyes on the street” (Jacobs, 1961), this part of the camp become more precarious as smugglers expanded their businesses to other profitable activities, for example by renting out appropriated abandoned shelters. As an answer to these crimes and the increasing pressure of the camp, more measurements of control have been taken. The pedestrian entrance on the side of the camp has been closed off, limiting the access to the camp to only the main one in the east and the back entrance in the west at the far end of the camp.

There used to be one volunteer who worked a lot with Utopia56, the organisation that was coordination the camp at that time. In Irak he worked with an organisation in refugee camps. In the end, the smugglers told him to stop working with the volunteers, because they saw it is a threat. In July, the most dangerous smugglers have been arrested. It is very hard with the smugglers, because in some way they offer the services that no one else can offer, but that all residents need, so it would be too simplistic to just condemn all of them.

Participation in the camp

Resident participation in the camp is important for both strategic and practical reasons: building capacity to post-camp (re)integration or reconstruction, the provision of dignity, a daily occupation and self-reliance (Stevenson and Sutton, 2011). Their presence in the camp showcases a willingness to take life in their own hands by leaving the precarious situation at home. The current situation restrains the residents down in these attempts. Participation can be a way to re-empower them, which will be beneficial for later reconstruction or integration. Participation should build on the existing capacities and potential of the residents as is done in slum upgrading programs. As resident rotation is high, the participatory process has to provide multiple and flexible options and alternative answers.

A Refugee Council was initiated by a group of highly skilled and residents in the old camp to represent and help the camp residents. In La Linière they had an adapted shipping container to hold meetings and run their activities. While they counted about 20 members from various backgrounds in April 2016, in May there were about a dozen left. Therefore they didn’t hold any more meetings at that time. It seemed the Council was very active in the beginning, helping to coordinate the aid initiatives and writing a letter after the death of a 17-year old refugee in a lorry accident to David Cameron and Teresa May to explain they are fleeing from the IS. In the letter they also invited them to visit the camp to see their situation. While this is a great example of participation, the council did not manage to last, given the many crossings.

The camp of Grande-Synthe is in strong contrast with the camp of Calais, also known as ‘the Jungle’. This informal settlement was originally self-grown. The political answer has been in sharp contrast with La Linière. After eviction of half of the site, a highly controlled container camp was set up by MSF. The limited number of places, the lack of these community facilities and the strict access control, make that most people still live in the informal part of the jungle. While the camp of La Linière in Grande-Synthe still faces many challenges, a limited level of participation and a certain level of control, it has shown that a more humane approach to dignity and autonomy is possible. The grassroots initiatives use an integrated approach that goes beyond the provision of shelter and basic infrastructure.

While today a massive evacuation like the Dunkirk Miracle in 1940 is not likely, the involved governments have to take their responsibility to provide an answer to this humanitarian disaster. Government initiatives and participation are essential and complementary aspects to provide humane, dignified and efficient aid.

Thank you very much, Hanne!

What did you think of this guest article? Please share your thoughts and ideas in the comment section below and don’t hesitate to contact me (laura@parcitypatory.org).