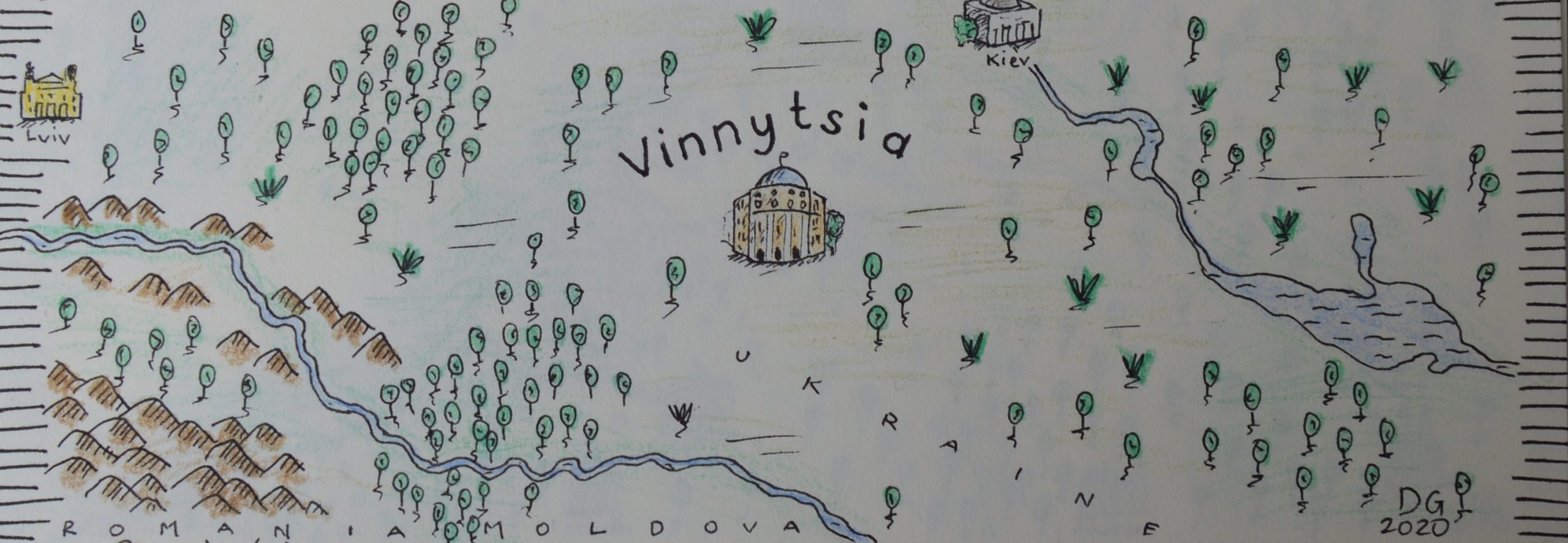

In the beginning of April 2017, I had the amazing chance to participate in a young researcher’s “Spring School”, looking into urban activism and participatory urban planning in the Ukraine. We met in a 300,000 inhabitants city called Vinnytsia in the West of the Ukraine, about 3 hours on the train from the capital Kiev. This was my first experience in a post-Soviet country apart from some short city trips and I have to say, it was like entering a whole new world!

I am used to participation becoming a norm in urban planning and being something desirable for many people. However, it seems that Ukrainians are rather skeptical when it comes to participating in designing their cities. Although public forums, voting processes and other participatory instruments are being created in the Ukraine, engagement is very low and I found out in conversation with many different people from Vinnytsia that there is little interest in taking part in urban planning. Reasons include that there is no culture of participation in the Ukraine (rather the opposite, a culture of top-down decision prevails) and there is little or no trust in politicians. The main bottom-up attempts at changing circumstances are found in petitions, which again give responsibility to politicians. A very low level of associational life and administrative difficulties like the need to have a permit for every gathering complicate urban activism.

In the following, I will attempt to describe some of the voices from Vinnytsia and surrounding cities.

Vinnytsia used to be an industrial centre under Soviet rule and has lost a lot of its importance. Recently, it is on an upward path again, gaining importance for start-ups and tourism. The 300,000 inhabitants are relatively poor with a monthly average income of 180 Euro. I was very surprised to see that there are areas without running water, making up up to 20% of a typical city.

Vinnytsia’s 2020 master plan focuses on strategic spatial planning, such as recuperating former industrial sites and providing more bridges across the river Bug. Currently, only three bridges span this wide river, of which one is under construction. The High Street in city centre has undergone a lot of improvements and now looks very impressive. There is some tourism potential in the city that Vinnytsia’s government is working hard to unlock. This includes the regeneration of waterfronts, as can be seen in the picture below. A fireworks machine creates beautiful shows during summer. However, this waterfront project was sponsored by Roshen, the Ukrainian president Poroshenko’s private chocolate company. This shows how politics, urban planning and private companies are intertwined in the Ukraine and explains some of the skepticism of local citizens.

During the Spring School, we visited two smaller cities outside of Vinnytsia but in the same region. Talking to local activists, almost exclusively women, was very insightful: It seems that while there are some ambitious projects like starting community parks, music festivals and art centres, there is little interest from regular citizens in participating in the process or even using the new infrastructure. A women’s group started a beautiful little library with colourful murals, an impressive collection of books that are available to borrow for free, and an array of courses for pregnant women. However, it is very hard for them to find neighbours who are interested in using these services. Even worse, their art centre is being vandalised on a regular basis.

Overall, my impression was that while there are some very commendable urban activism initiatives by local residents (mostly women), there are even more obstacles when it comes to maintaining the projects and generating a public interest in them. Funding is not difficult to acquire, since many Western European countries provide generous support. The problem is to convince fellow citizens of the value of urban projects and of participating in communal activities.

During the Spring School, we therefore discussed the question of how to incentivise participation and urban activism. We tried to understand when and under which conditions people participate and came to the conclusion that it is very important to have a culture of participation and trust in politicians and urban planners. It seems that this process is only very slowly starting in Ukrainian cities like Vinnytsia. Participatory urban planning has arrived at city planning level and there are many offers of public forums and other participatory tools. However, low attendance rates and a general disinterest make it hard for activists and planners to go beyond the level of informing the public. Thinking of Sherry Arnstein’s ladder of participation (see this article for more on this), non-participation and maybe tokenism are currently the highest rungs achieved. There is much more work to do when it comes to participatory urban planning in the Ukraine. These are my open questions:

- Can post-Soviet countries like the Ukraine learn from other countries, for example Latin American ones, when it comes to a culture of participation and a sense of entitlement towards the city?

- Or is it rather a question of waiting for urban activism and participation to either become more popular at some point or fade out completely because they are not appropriate in these contexts?

What do you think? Please share your thoughts and ideas in the comment section below and don’t hesitate to contact me (laura@parcitypatory.org).