Introducing Old Fadama

This article is based on my own Master’s dissertation from August 2017. I will give you a summary of my research results, drawing on interviews I led with local experts, who at their wish remain anonymous.

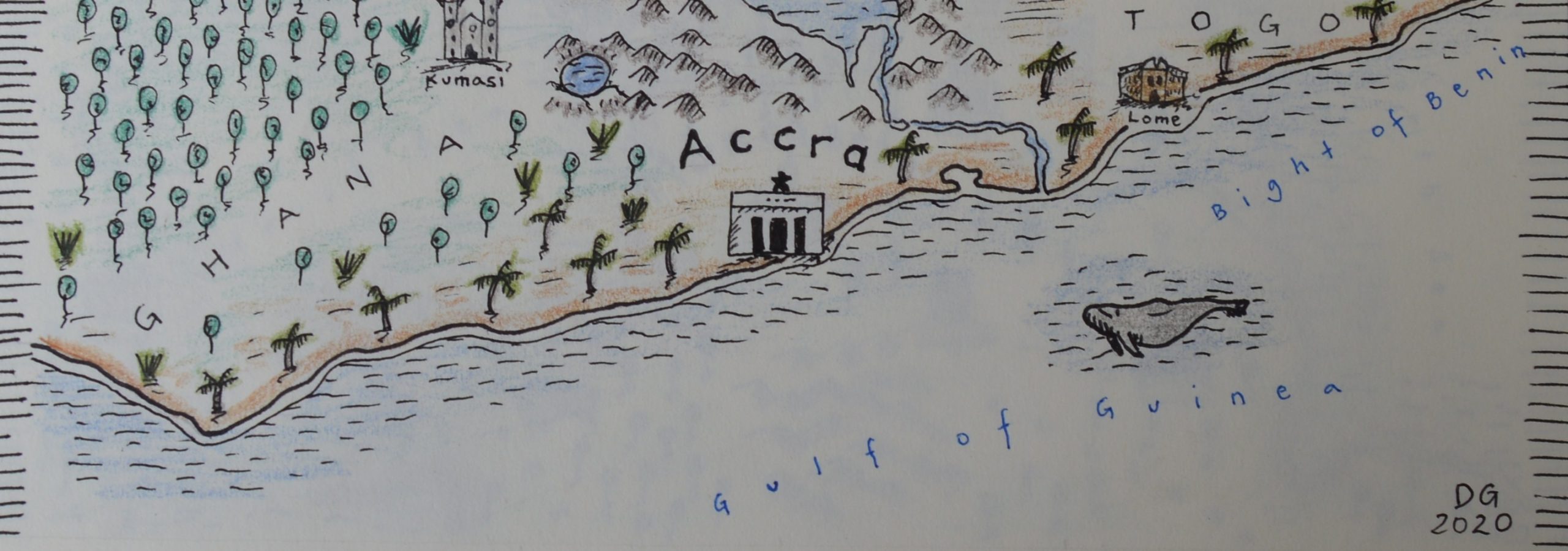

Old Fadama or ‘Sodom and Gomorrah’, as it is also known in Accra, is one of Africa’s and certainly Ghana’s largest informal settlement or slum. Roughly 200,000 people live near the Korle Lagoon and its tributary rivers in what is now Accra’s city centre. The settlement has been subject to various eviction attempts ever since its existence.

Old Fadama first grew in the 1980s by war refugees from Northern Ghana. In the years before that, the area had become a small settlement already due to increased urban growth in Accra. Over the last decades, there have been multiple attempts by the government at evicting the dwellers of Old Fadama. Starting in 1993, when 400 households were evicted, and continuing in 2002 and 2012, numerous inhabitants of Old Fadama have been forcefully removed from their homes. At the same time, the vast majority has stayed where they are, which is a point of big interest. How was it possible that they remained living in their houses despite the government’s strict intentions to knock down the entire settlement?

Official reasons for eviction

All around the world, evictions usually happen for similar reasons:

- value of land

- image of the city

- health and safety concerns

- environmental concerns

Old Fadama is a prime example. With Accra being a growing city of global importance, the government is set on beautifying its city centre and making it more attractive for tourists and businessmen alike.

One interviewee who lives in Accra told me:

“My last visit is three or four years ago, but the settlement maintained the same character of being a ‘ramshackle facility’. It is a very resilient settlement. In 2003, I did my undergrad and found out that relocation would be the best option for OF, but the residents didn’t like this idea since it involved moving away from their valuable central location. At the same time, you have to admit that the place itself is not good for human habitation since there is no drainage system and it is too close to the sea. So, it is very hard to find a good solution. There is no urban planning in place and the settlement is already too crowded, meaning the land cannot really support this many people. A potential solution would be to provide schools, bath houses and toilets.”

The value of the land Old Fadama sits on has increased drastically, since it is now located right next to the Central Business District of Accra. At the same time, there have been long-lasting, but to date unsuccessful attempts to clean up the Korle Lagoon to the other side of the settlement. Measures to ‘clean up’ include the relocation of residents of Old Fadama. Lastly, there are health and safety concerns related to the dirty water of the lagoon and to the presence of diseases within the settlement – “prostitution and crime exist like anywhere else”, one expert told me.

Notwithstanding all these reasons, eviction remains a deeply unfair and actually illegal action that counteracts human rights and various other treaties that most countries, including Ghana, have signed. This includes the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights with long lists of housing rights as well as the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (the right to dignity and the right to an adequate standard of living are directly violated by evictions). As opposed to upgrading or relocation attempts, forced evictions leave residents without even a temporary housing option provided by government. They often receive the notice very shortly before the actual eviction takes place and lose not only their home and their neighbourhood, but sometimes even part of their belongings.

Derogatory discourse: Labelling Old Fadama as ‘Sodom and Gomorrah’

Under Mayor Vanderpuije (in office from 2009 until earlier in 2017) and in combination with urban growth all over Africa, which resulted in books like Mike Davis’ pessimistic account of the ‘planet of slums’, eviction attempts became more frequent and language in public discourse and in politics turned against Old Fadama by labelling it as ‘Sodom and Gomorrah’. This biblical name evokes a city of evil, of prostitution, sodomy, poverty, dirt and vice. While there is prostitution and criminality in Old Fadama, their prevalence is not more striking than in similar settlements. The e-waste site next to the settlement at Korle Lagoon is another factor that might have inspired this pessimistic name. However, it is not part of Old Fadama and is in its own right an important contributor to local economy.

Residents took to the roads in order to protest against this name. However, it seemed for a while that Vanderpuije and his government had reached their goal of thoroughly bad-mouthing the settlement. Middle class and media were on the side of the government and insisted on evicting Old Fadama, since it was seen as a ‘blemish’ on the city, which at the same time aspired (and still does) to be a global city. This neo-liberalisation always plays in the hands of eviction attempts and is one of the main reasons for forced eviction, though usually covered by phrases like ‘unlock valuable land in central areas of the city’.

Residents prefer the term Old Fadama and were of course very aware of the consequences of their new nickname:

“This labelling uses a heavy term, considering that God destroyed Sodom and Gomorrah. This constitutes a deliberate attempt to portray Old Fadama in a certain light, forwarded by Mayor Vanderpuije. This discursive framing then provides legitimacy for forced eviction. This ‘being outside of the law’ is a justification.”

Meanwhile, the government, especially since 2009, promoted the term ‘Sodom and Gomorrah’ to justify evictions. This is the core of my dissertation: How do governments try to influence public opinion to justify actions like forced evictions and how can the residents of informal settlements resist? Interestingly, this influencing of the public is a trend visible all over the Global South (and the Global North too!): By bad-mouthing and criminalising certain districts or housing projects, public opinion turns against them so that settlement dwellers lose middle-class citizens as potential allies. The opinion of the press is crucial here, since it influences, but also mirrors public opinion. Old Fadama is an example of how to turn this opinion around, thus making it much harder for officials to follow through on the eviction plans since they are now being criticised, observed and protested against.

Eviction attempts over the years

Old Fadama’s residents have a history of speaking up for themselves and they can count on reliable support from Slum Dwellers International (SDI) and other local organisations present in the settlement. When the government announced the eviction of the entire settlement in 2002, they became active and conducted a large-scale enumeration project, thus providing evidence of the number of people living in Old Fadama as well as their occupation and their essential importance for the economy of the city (for example, some of the most frequented markets for fresh produce are in Old Fadama). They even went to court with the help of the Centre of Housing Rights and Evictions (COHRE), but lost the case. Still, evictions did not take place.

Renewed announcements for evictions in 2009, when Mayor Vanderpuije took office, were met with large-scale protests and another enumeration. Two years later, when the Korle Lagoon Restoration Project was due to start, residents tried to show collaboration by relocating parts of the settlement that were located very close to the lagoon. However, in 2012 and in 2015 large evictions took place again and coincided with fire disasters as well as floods. According to Ghanaian law, a settlement becomes legal after having been occupied by a large group for 12 years In June 2015, up to 2,000 households were forcefully evicted with no or very little notice to avoid the legalisation of Old Fadama, which by then officially existed for 12 years. The first enumerations of 2002/2003 were used as a basis here.

Opinion turns – back to ‘Old Fadama’

Interestingly, the 2015 evictions were also the trigger for some changes regardingthe degree of resistance. Residents naturally got very upset and protested in front of the State House.

Media interest, which before mainly focused on abject poverty and gruelsome living conditions reported to them about ‘Sodom and Gomorrah’, increased and for the first time, reporters actually came to the settlement to see what was happening. The Slum Union of Ghana, founded in 2012, was also very active. As one interviewee described it:

“The Slum Union has been instrumental in mobilizing residents of slums for mass protest against eviction in the past. The Union has also represented these slums in the media, explaining the problem from the point of the slums. The media campaign against eviction has been very successful attracting the attention of stakeholders to work on providing solutions.”

In a discourse analysis, I try to compare various local newspapers to see how their reporting changed. And indeed, in 2015 and ever since, wording has changed away from portraying victims living in hell towards self-empowered individuals or ‘agents of change’ living in “Sodom and Gomorrah, properly referred to as Old Fadama” (quote from pulse.com).

Another part of the resistance strategy is the use of political connections, as this interviewee describes:

“Residents basically use their political connections to resist the evictions. They do this by calling on political leaders from their constituency. During the 2015 eviction, this was the first strategy used. But that only halted the eviction for one day. The other method that was used is the mass protest approach. Residents mobilized themselves and confronted the government security. Some of the matched to the presidency and others matched to the Parliament House. Some state properties were destroyed and so there was a national security concern. The government then ordered for the demolition to stop to prevent escalation of violence protest. The other strategy was the use of social media to publish this ‘Human Rights abuse’ to the internal media in other to give it internal attention.”

Apart from using political connections, negotiating, protesting and managing to change the discourse in local media, residents of Old Fadama also started to organise local theatre plays and run their own radio shows. This is what I call ‘active citizenship’ in my dissertation, because even more than claiming their Right to the City, their right to living in this settlements, residents actively work on changing outside perspectives. Thereby, they create news spaces, both abstractly in discourse and physically by inclusive place-making. This goes beyond the Right to the City, which is not necessarily applicable in informal residents, since it ultimately requires a change in legal circumstances and in the neo-liberal system. This is something that residents can most probably not achieve, especially facing every-day threats such as evictions. However, active citizenship and the creation of new spaces or the change of discourse are much more in their reach.

One interviewee told me how these new spaces are manifested even physically in building structures:

“Along the path of the 2015 eviction, there are now cement structures being built or built already. This shows how people are self-assured and you might even consider it as a way of preventing further evictions, just the building material itself. There is a certain resistance in the material.”

Summary: From Old Fadama to Agbogbloshie and back

Of course, Old Fadama is just one of many examples for forced evictions and although many stories are similar, they are never the same. Still, I tried to deduce some more general advice or lessons learned, since after all the residents of this particular settlement have been quite successful in remaining on the land that, according to human rights as well as the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights, they should be permitted to live on. At the very least, they must not be forcibly evicted.

It appears that it is crucial to draw media attention to the unfair act of forced evictions and to have the sympathy of the public on one’s side. A mix of strategies, including the use of political connections, mass demonstrations, protests, legal negotiations with the help of SDI and other NGOs and media action promises to be the most effective way to resist evictions. This will make it much harder for the government to conduct unfair evictions. At the same time, it is necessary to promote a systemic change, such as a semi-formal system of land tenure and a stronger lobby for the rights of people living in informal settlements, as initiated by Ghana’s Slum Union. After all, Old Fadama’s residents and those of countless other informal settlements worldwide remain in danger of forced eviction.

Another big thank you to the interviewees and all the people who supported me in my dissertation! I hope you enjoyed reading about it. There will be another article about the Right to the City (and beyond) soon.

Please share your thoughts and ideas in the comment section below and don’t hesitate to contact me (laura@parcitypatory.org).