The rise of smart cities in India and Africa

There are now “widely circulated images of slum dwellers using mobile technologies to improve daily lives” (LSE 2016). Does this represent smart participation of citizens in smart cities?

Smart cities has become a very powerful buzzword in recent years and with programmes like India’s “100 smart cities”, first steps are being made towards cities that are much smarter – even in countries which are not highly developed on a technological level. Afro-smart cities, as described in this LSE article, are on the rise as well. Their digital revolution can be used as a very good stepping stone for the advance of smart cities, although this needs to be viewed with caution at the same time, since the interests of corporate big firms do not always comply with the needs of city planning or the interests of average citizens.

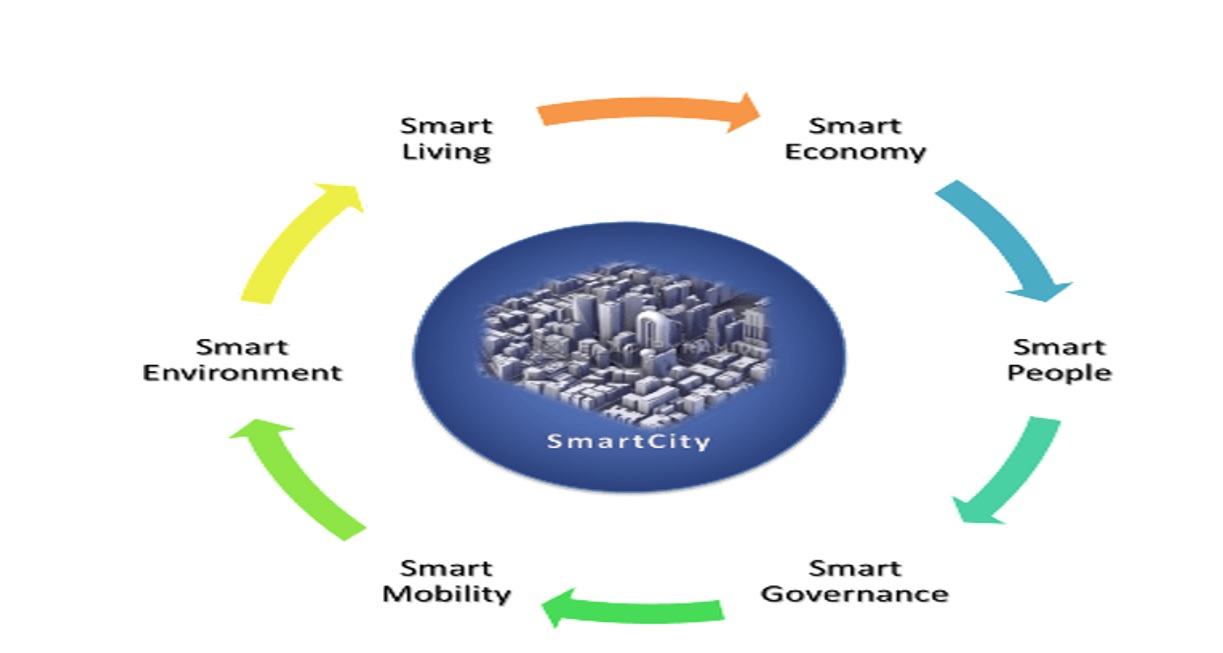

What exactly is a smart city? It has digital technology embedded in city functions to improve the quality of life and support a clean and livable environment. This includes not only technological innovations, but also factors like health care or water supply. Experts promise that especially people from poor urban backgrounds can access smart technologies and thus participate in crowd-sourcing and open-source local governments and urban planning projects.

In this short article, which is based on a presentation I gave together with Nokuthula Mnyandu a while ago at Berlin’s Freie Universität, I would like to introduce you to the topic of smart governance and smart participation – which, as you can see from the graphic, also requires smart people.

An e-government promises to be better positioned to promote human development and ensure good governance, as well as being more responsive to citizen’s needs and inputs. Here, information technology comes in to enable “smart citizen participation”. This is considered to make the political process more inclusive, accessible, open and responsive.

E-Participation Tools

You might have noticed that most pictures or visualisations of smart cities do not include people at all, since we are not typically perceived as part of the automised, technologically-driven city. Rather, the smart city helps us to be less human or less full of flaws. However, considering that a city is made by its people, it is crucial – at least in my opinion – to include smart means of participation. Read this article in which I describe my impression of a smart cities conference.

Smart participation or e-participation (e for electronic) means that there are tools available for a better and citizen-centred mode of governance. This is probably the only element of the smart city that directly puts the citizen at the centre. By using information technology, the smart city supposedly responds better to citizens’ needs and inputs. An example for that is the smart voting box installed in South Africa’s Cape Town called “Your City Idea”.

Other tools for electronic participation could include voting apps, feedback machines (like the ones you see in airports to rate the cleanliness of a bathroom, for example) and other means of collecting ideas. Civocracy is a good example for how to establish a digital link for improved communication between a government and its citizens.

What makes participation smart?

I would say that an inclusive, open, responsive and deliberate process that empowers all citizens to participate is crucial to make a smart city work. Smart participation has to go beyond token participation; it has to really give power to citizens. A good example for that is particypatory budgeting, which not only puts people at the centre of decision, it also counteracts corporate interests and helps to reflect on-the-ground needs and desires of average citizens.

Ideally, e-participation helps to reduce the so-called digital divide by improving citizens’ access to services like free internet, better networks or publicly available computers. Cell phones are so widely spread nowadays that they can also empower large numbers of citizens to participate via apps or the internet, thus helping in bridging the divide between the rich and the poor. This also includes a divide of information.

Smart participation also helps the government to improve its services and to better understand citizens. However, there is a big danger of management failure and of course, no one forces the government to listen to potentially uncomfortable truths. But this is where e-participation can use its feature of being electronic, or digital: By bringing issues to social networks and other easily accessible platforms, it is becoming much harder for governments to look the other way.

E-readiness

However, the degree to which participation can be satisfactory is also determined by how smart citizens are, in the sense of: do they know the value of participation? Do they know participatory techniques and how to access them? Are they ready to participate – do they have time and ideas? Are they brave enough to voice their ideas?

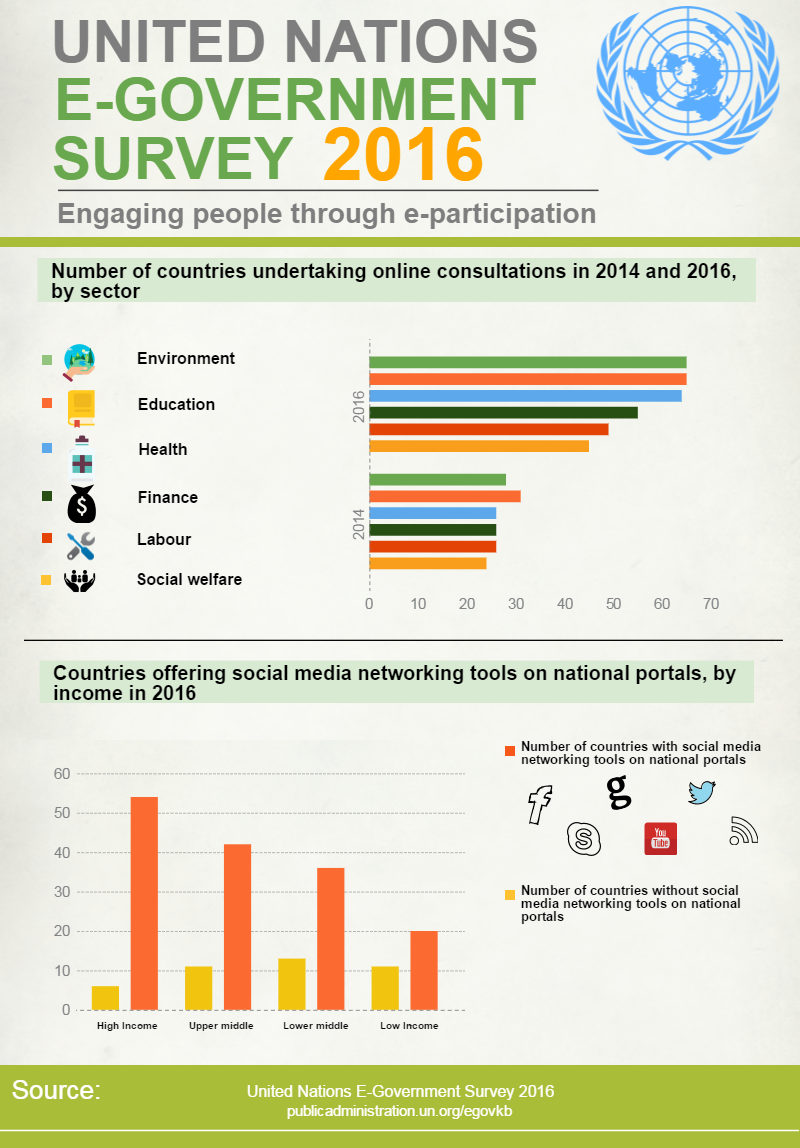

In order to measure this, the United Nations have developed an index to show a population’s readiness for e-participation and e-governance. This index measures web presence, the quality of telecommunications infrastructure and human capital and also includes indicators from the Democracy Index and the Human Development Index. Not surprisingly, many European countries as well as the US and Australia lead this list, but countries like Kazakhstan, Argentina and Qatar are also included in the Top 50 countries ready for e-participation in 2016.

Apart from the e-readiness, the extent to which a country is ready for smart participation also depends on the existing culture of participation and on factors such as presence in social media or literacy rates.

Even in the best of cases, it is hard to find perfect examples for participation. Therefore, smart participation should actually learn from the mistakes of past participatory practices and use its technological benefits to fill in the gaps, where needed.

Can smartness actually improve participation?

While buzz words like accessibility, involvement in the urban sphere, audience and mobilisation are being thrown around in the discourse on smart cities, Nokuthula and me argue that smart city technologies can actually increase involvement in online participation.But at the same time, smart technologies for participation can be highly exclusionary. It is not just the urban poor or those that cannot or do not use the internet, but also rural populations, who are being excluded from being a smart citizen. Access to smart technologies (and therefore smart participation) is often very restricted. Elite politicians and big technology companies typically follow their own interests and even find ways to practice online discrimination when deemed necessary. The promise of smart cities and smart participation needs to be questioned. What are the implications of this new mode of participation, if it even works?

Even if enough people participate online in political and urban planning decisions , and even if the government listens to citizens’ ideas and suggestions, there is still the question of who is actually participating and how this can be integrated into the broader political system. E-Participation is a question of good technological management, of trustworthy engineers and software programmers, and in the end of political will. Fragmented municipalities and government structures that are not working offline will not suddenly start working online!

It is therefore important to stay skeptical and not trust too much in the promises of smart cities and smart participation, simply because we do not know yet what they entail. While smart participation can be used to make participation more inclusive and to fix some past mistakes in the practice of participation, we need to keep in mind that the quality of participation depends a lot on political will, participatory cultures, corporate interests, the education of citizens and, as a novelty, on the digital divide. Can technology increase participation? Or can participation actually improve technology?

Maybe the Smart City Africa Conference in May 2018 can give some answers.

Please share your thoughts and ideas in the comment section below and don’t hesitate to contact me (laura@parcitypatory.org).

Header Copyright:Accra Airport City by Kwasiok via Wikimedia, CC BY-SA 4.0

One Response

Thank you for this important argumentation, I fully agree. I would also add that smart participation, as any other forms of participation largely depends on the competences of the people: their knowledge about their rights for making their words heard, their competences to set up their goals and priorities, as well as to formulate their argumentation for supporting these goals. This is why I consider that learning, and knowledge transfer are also key issues of smart participation.