Building resilience through participatory mapping in informal settlements in Brazil

Written by Carolina Monteiro de Carvalho. Carolina developed a postdoc research using Participatory Geographic Information Systems (PGIS) applied to urban governance, at the Public Health Faculty (University of Sao Paulo, Brazil) and Aalto University, Espoo, Finland. Currently, she is a researcher at the Institute of Environment and Energy, of São Paulo University, and a consultant in Participatory Mapping. She blogs here.

Social inequalities are becoming apparent now more than ever due to the COVID-19 pandemic. In the peripheral metropolitan areas of developing countries, tools that promote social inclusion and sustainable urban planning are urgently needed. With these tools, citizens can communicate their demands more effectively to the city authorities. This allows for strategies and actions to be developed, so that they can address inequality problems.

The participatory mapping method presented in this case study, which integrates Participatory Geographic Information Systems (PGIS), consists of a powerful tool to stimulate participatory processes among different social actors. It places a special focus on traditionally marginalised social groups, such as the elderly, children, adolescents, women, low-income groups, etc., developing territorial approaches that enable intersectoral dialogues relevant to sustainable development and the reduction of inequalities.

Participatory mapping aims to represent local knowledge by applying geo-technologies and mapping techniques that facilitate an informed urban planning design, the development of strategies and interventions on urban structure, the decision-making processes and that also support the city’s communication. Local knowledge is extremely important for the urban planning process and development, since nobody knows the neighborhood or city as the citizen who lives there do. The participatory mapping process also has the advantage of empowering citizens in geo-spatial techniques, stimulate dialogue, and thus, increasing socio-environmental awareness and consequently, resilience, when the needs and problems faced by a social group are mapped out, and appropriate action is taken. Therefore, this method has great potential to make social change.

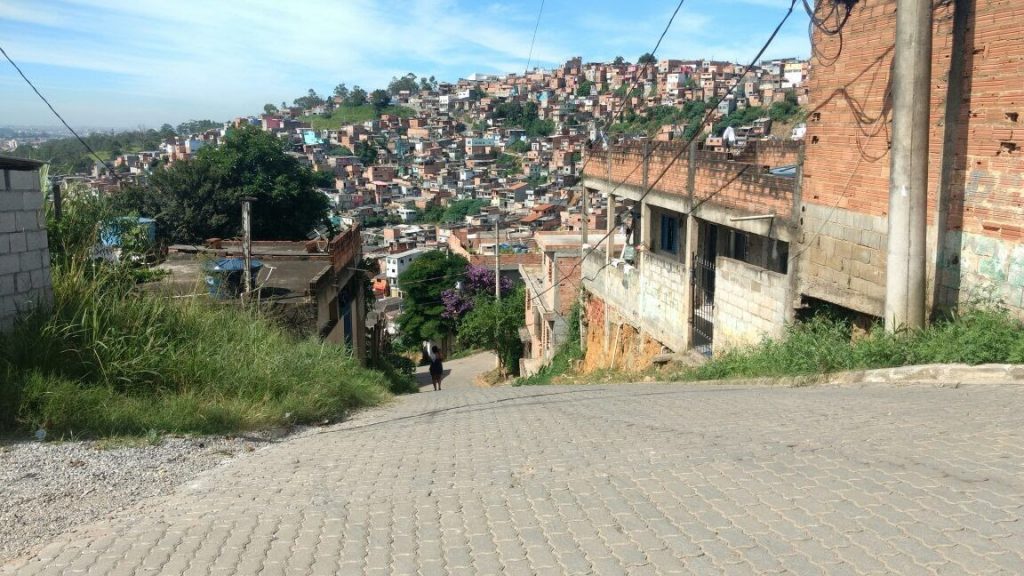

My post-doctoral research involved the application of participatory mapping to investigate the access to basic resources such as water, energy and food (WEF) by the Novo Recreio citizens, a peripheral neighborhood of Guarulhos city (São Paulo state, Brazil), as part of the Resnexus, which study the interdependence among these basic WEF resources and urban sustainability. Guarulhos is a highly industrialized and urbanized city bordering São Paulo, and suffers from several social and environmental impacts.

The Novo Recreio neighborhood is located in a region of mountains, being an area prone to erosion and landslides when heavy rainfalls occur. Novo Recreio is home to approximately 4,500 families, facing several urban problems, such as access to fresh food, water and energy, mobility issues, and insecurity. Waste is also a problem, since there are several inadequate waste disposal spots there, increasing the incidence of diseases and other environmental consequences.

Participatory mapping was applied in the format of an extension course for the community, with a certificate of the University of São Paulo. The course was offered to adolescents from 14 to 17 years old, who had previously attended the local NGO “Clube de Mães” in the period of April-August 2017. This NGO hosts families for educational and professional activities. Registration for the course was open to adolescents who attended the NGO’s events. The main objective was to introduce the fundamentals of mapping and planning practice to promote awareness and socio-environmental reflections, in the first place. Besides the participatory mapping activity, other typical participatory research tools were also used to stimulate dialogue.

In the progressive development of the course, there was a preparatory phase, which provided basic information on mapping and also on the surroundings of the area, with a group pre-mapping exercise. Participants were able to identify rivers, the environmental protection area nearby, their homes, and daily routine in the neighborhood. This step is called Sketch Map, and they provided an initial diagnosis of the main problems and what the participants would like to expect from the neighborhood in the next years.

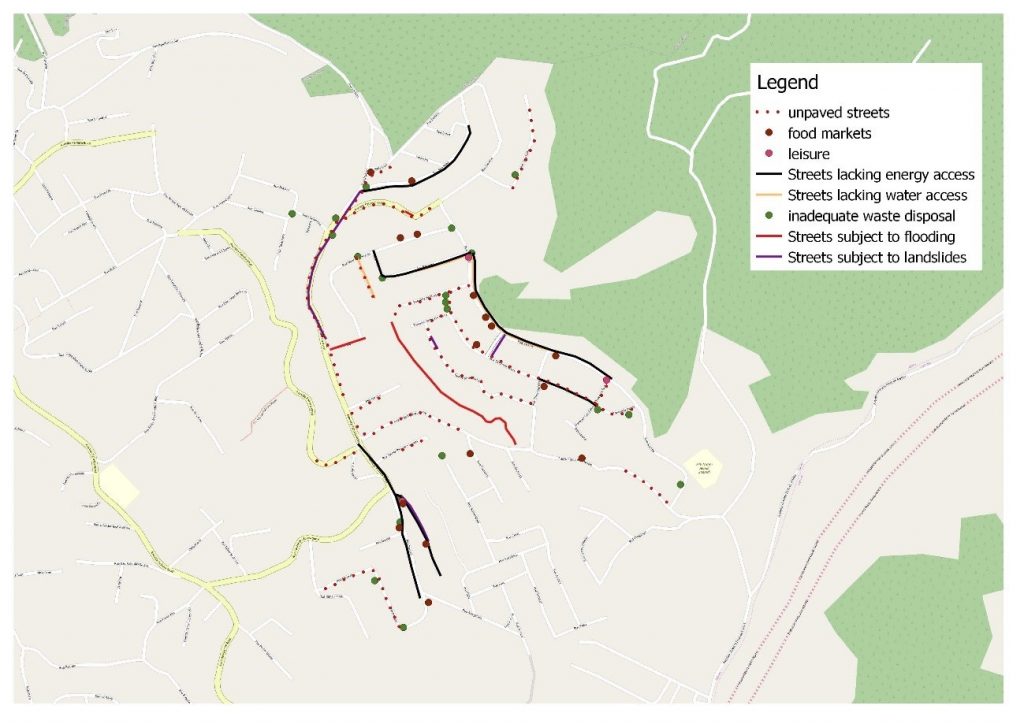

The next group mapping phase provided more accurate geoinformation and location of the socio-environmental problems mentioned in the preparatory phase. With this mapping process, places with socioenvironmental problems were mapped, such as those with potential for landslides/flooding and inadequate waste disposal, or areas where these problems overlap, representing a risk to the health and safety of local dwellers. Besides, the discussion to mark each point on the map was a rich process, that promote empowerment and awareness.

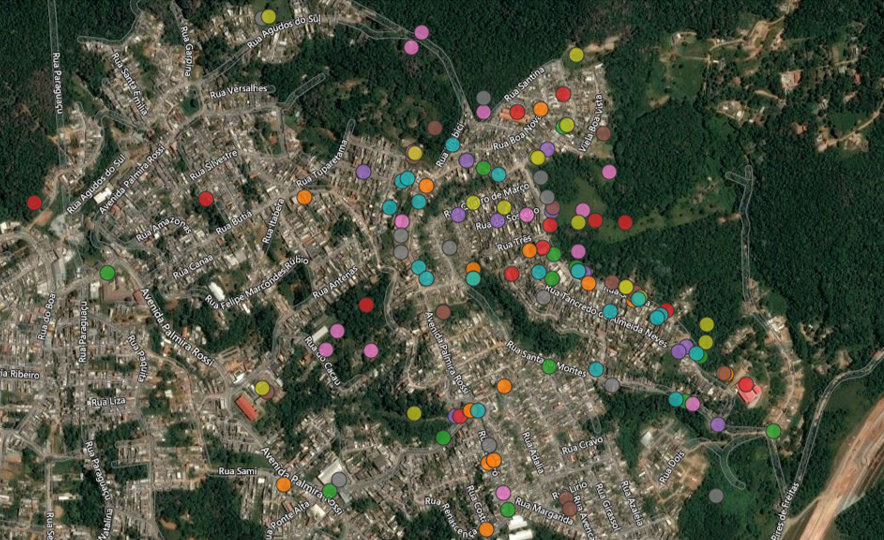

As a final exercise, the online participatory mapping platform Maptionnaire, provided by Mapita LTD, Finland, was used in the course aiming to plan a new neighborhood. A survey was builded with the platform, and questions were answered on the platform, that presents a MapBox framework, and therefore, geolocates all the mapped features as points, lines and polygons. The following questions were answered by the participants and are colour-coded in the map below:

- Where do you live? (turqoise)

- Where would you like to have a school? (yellow)

- Where would you like there to be a cinema/theatre? (grey)

- Where would you like there to be a club? (pink)

- And a court? (brown)

- Where could a recycling cooperative be set up? (purple)

- Where would you find it appropriate to set up a shelter in case of heavy rain and landslides and residents need to leave their homes? (red)

- Where would you like to have a fair? (green)

- Where would you like to have a health centre? (orange)

- In your opinion, what should be done to make these measures a reality?

Answers were the mapped points below, and those provided a new insight on the future neighborhood planning.

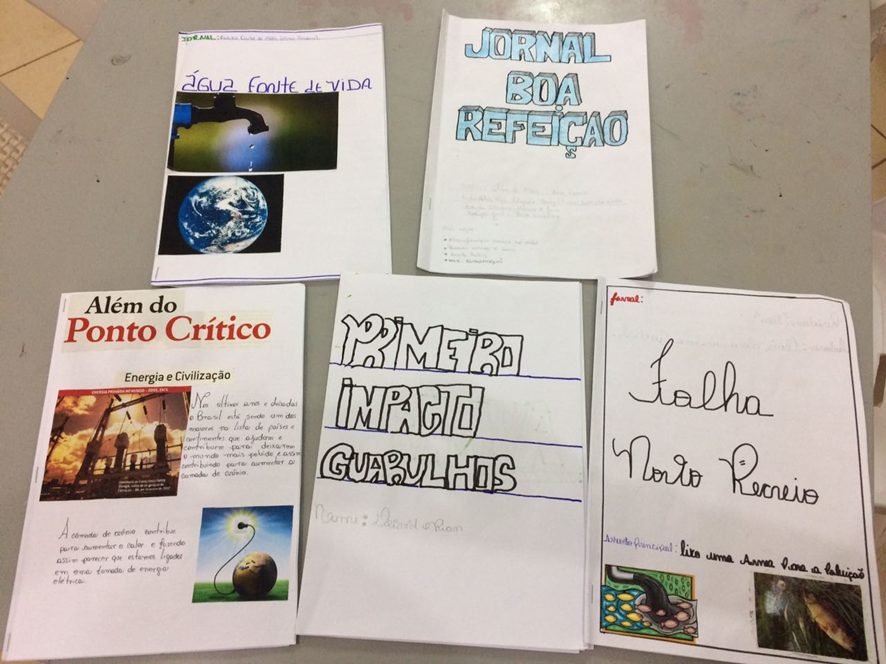

The post-mapping phase provided a reflection on the new discoveries and mapped points and their impacts on their lives, and suggestions for overcoming these problems came out, with the application of other participatory methods, such as the integrated panel and the development of community journals, in which the problems discussed were reported along with possible solutions. The role of the community journal is to communicate to the neighborhood everything that was discussed during the mapping process.

After the participatory approaches were applied, the produced material was disseminated to the community and the society of Guarulhos through project workshops, meetings side-by-side with other stakeholders, articles and other publications, like blogs, and social media, helping to spread the message that adolescents from peripheral areas are capable to produce new urban knowledge and recommendations that should be taken into account in urban planning.

Other projects like this one are being developed, and you can take a look on the author’s blog to know more about participatory mapping in vulnerable communities.

Here is a guide detailing more in-depth the approach described in this blog post. Please download it here (English version).

The participatory socio-environmental mapping developed in the city of Guarulhos, São Paulo was developed with the support of the School of Public Health (São Paulo University), supervised by prof. Dr. Leandro Giatti, Prof. Dr. Marketta Kytta (Aalto University, Finland), Prof. Dr. Nora Fagerholm (University of Turku, Finland) and Mapita Ltd, which provided us Maptionnaire license. Funded by FAPESP 2015-21311-0.

Thank you, Carolina! Here is a related blog post to learn more about mapping: