Written by Dennis Gastelum

This essay was part of a seminar at the University of Manchester in summer 2017.

Introduction

In 2015, Berliner Verkehrsbetriebe (BVG) -Berlin’s main transport company-, along with the comedian Kazim Akboga, launched a video campaign to celebrate the welcoming and tolerant Berliner way to be. ‘Is mir egal’, which roughly translates as ‘I don’t care’, is a collage of awkward situations that might only be tolerated and even encouraged in Berlin’s public transport system. The campaign showcases the fact that Berlin is an open city that tolerates and welcomes all kinds of people, especially those that have something creative to offer. The video finishes with the motto ‘Nur wir lieben dich so, wie du bist’ or ‘only we love you the way you are’. This video is part of a broader strategy that places Berlin as a city with a creative and stimulating atmosphere where diversity is accepted and sought-after.

In this essay, I will explore this vision of Berlin as a creative open city and its implications for urban planning and development. First, I will introduce Berlin as a creative city and the fact that creativity has been used by the Berliner authorities as a strategy towards economic strength. Then I will focus on the role of interim uses of places or Zwischennutzung as stimulators of creativity and creators of creative space. I will carry on by contrasting this creativity trend with the significant issue of gentrification. This section links Berlin’s place marketing with an undesired rise in the land price. I will touch upon equal access to housing and green infrastructure as an example of inequality fostered by the quest of attracting middle- and upper-class creative individuals. Then I will explore the link between Berlin’s attractiveness for creative people and equality as the core of an inclusive creative city approach. Finally, I will connect Berlin’s case to an upcoming case of a creative city in the Global South. I will claim that Zwischennutzung strategies can be useful in environments that have relatively relaxed regulations such as the case of Guadalajara, Mexico.

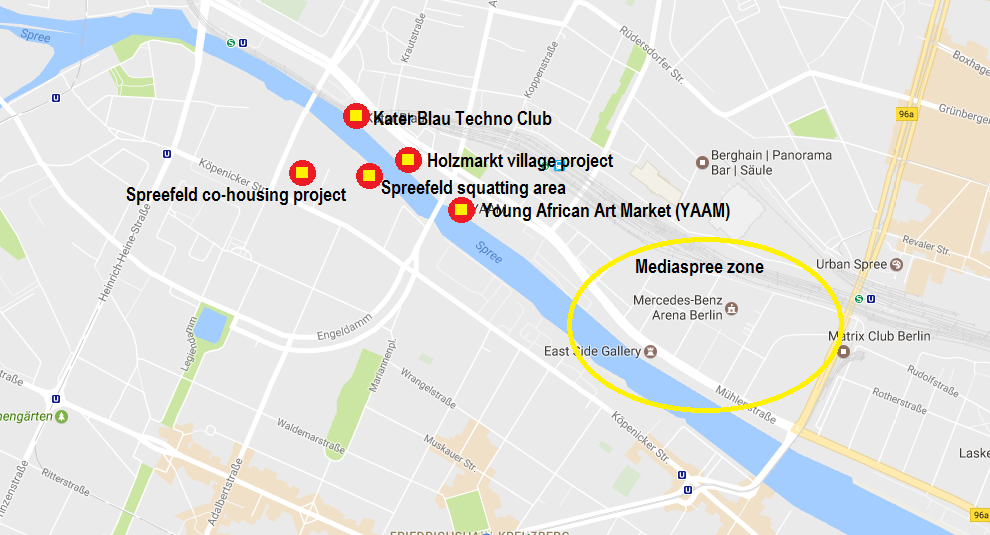

A map has been included the location of the examples utilised in this essay. This map depicts a highly contested area in the Friedrichshain-Kreuzberg, which is relevant for this essay’s purposes.

Berlin as a creative city

Public policy has increasingly incorporated the role of production of urban images, advertisement and communication into its agenda, especially in cities of North America and West Europe (Colomb 2011). The city of Berlin has been considered as a creative city, which can be defined as a place where outsiders induce change through the communication and support of ideas (Hall, cited in Jakob 2010, p. 197). This section of the essay will analyse Berlin as a creative city and the implication that it has for urban development and interim places. I will then continue with the generated pressures on land use in the city.

In Berlin, the approach towards empty brownfield spaces in the 1990s included the construction of places such as Potsdamer Platz as a signal of strength of a global metropolis in a new era. This was one of the largest building sites in the history of Europe and its impressive grand architecture is a reflection of Berlin’s desire to show itself as a strong and resilient city in the reconstruction phase. Starting from the early 2000s, Berlin’s official promotional discourse has included activities, sites and places that were not part of the early post-unification era (Colomb 2011). This new discourse has been harnessed to urban development policies, as the discourse includes a sense of creativity, ‘unplanningness’ and dynamic diversity that has permeated the city’s urban tissue. This shift came at the dawn of the 21st Century, as a strong mobilisation of temporary uses of land became the staple of the city’s approach towards empty sites.

This vision of Berlin as a creative city is expected to continue, as the city’s strategic urban development vision towards 2030 recognises the role played by creativity in the unleashing of economic strengths of the city. In this sense, creativity has been addressed as a strategy to strengthen the city’s position as a competitive and attractive urban destination (Senate Department for Urban Development and the Environment 2013). The search for stable growth and the substantial role of technology and innovation in achieving it has created an inertia that places creativity at the core of the reputation of Berlin as a global city. In order to offer adequate venues to welcome creative and cultural individuals and businesses, “there are plans to set up a public-private space exchange to facilitate the interim use of open spaces and premises” (ibid, p. 33).

These interim uses are referred to in German under the term ‘Zwischennutzung’ and include a series of activities such as techno clubs, beer gardens, waterfront spaces and flea markets that have been planned “from the outset to be impermanent” (Haydn & Temel, cited in Colomb 2012, p. 135). The existence of vacant sites and wastelands created spaces for these activities to take place throughout the city. A visit to the co-housing project at River Spreefeld (see map) offered an example of this kind of activities.

While the housing project itself does not illustrate the existence of interim spaces, the site right across the river is an example of Zwischennutzung. Although the existence of a techno club in the location, known as Kater Blau (see map), is widely accepted by the neighbouring areas, issues regarding constant changes in the line of businesses and noise complaints exemplify the ‘informality’ of the site and its nature as an impermanent location. This techno club is located in the same area as the creative cooperative project known as Holzmarkt village (see map), which I will touch upon later on when discussing conflicts. Another example of pop-up situations that fit into the Zwischennutzung concept is the Young African Art Market (YAAM) (see map), which we visited on the same day to have lunch and functions as a beach bar, sports venue, party hall, restaurant and community centre altogether. It reflects the widespread existence of interim use space in the city.

Creativity and gentrification

Notwithstanding the pop-up nature of these projects that intend to foster the creative lifestyle of Berlin, a heavy gentrification wave has hit the city in the last decade after the ‘Berlin-boom’ that celebrates Berlin and its lifestyle (Balicka 2013). This process of gentrification might be explained in light of the conflicts in the branding strategy of the city, as suggested by Colomb (2012). The author utilises the framework created by Bader and Scharenberg (2010), in which branding strategies clash with their very own aim of sustaining the creative process. In this sense, the branding strategy of Berlin as a creative city has enhanced the city’s symbolic value, but has also weakened everyday conditions that are vital for the sustainability of the creative process itself. In other words, it threatens “the survival of temporary, experimental uses, forcing them to transform, relocate, or disappear” (Colomb 2012, p. 147) This process has then encountered the exaltation of capitalist urban development that has the search for ‘monopoly rents’ as a characteristic (Harvey, cited in Colomb 2012, p. 144), which has brought about the gentrification upsurge.

As part of this conflict dynamics, the area known as Mediaspree (see map) offers a good example of a development initiative that has become a hotspot of public contestation and demand. Mediaspree can be simply defined as a mega redevelopment of the river banks of the Spree, around the area of the East Side Gallery, which we visited. It responds to business and real estate interest, as shown by the fact that even a section of the East Side Gallery, a memorial to the city’s troubled separation, has been torn down to allow residents access to the luxury apartments. This picture shows a large concentration of cranes in the area that will become a shopping mall around the already built Mercedes-Benz Arena, both part of the Mediaspree venture:

So far I have talked about gentrification as an uprising issue in the Berliner scene and the public effort to address the devolution of private development areas to the people, all of which is related to the discourse of Berlin as a creative city. This process is associated with the observed housing market boom that has brought about a rise in housing prices, especially in central districts of Berlin (an de Maulen and Mitze 2014). As explained by Dr. Cordelia Polinna (2017) in her presentation about the challenges of urban development in Berlin, there is a competition between uses –residential, commercial and industrial- that has generated pressure on the housing market and the rise on housing prices. This phenomenon is part of the decoupling between the real estate market and reality. According to Dr. Polinna, affordable housing is a priority already being addressed by the social housing provider GEWOBAG, along with a reuse of the existing inner urban fabric of the city. This pressure has been further aggravated by the arrival of refugees in Berlin, particularly in 2015.This project is highly contested, with the aforementioned Holzmarkt village as an example of the resistance against the privatisation of the riverbank intended by Mediaspree. Regarding this resistance, and specifically a citizen-based referendum about the opinion on Mediaspree in 2008, Ahlfeldt (2010) claims that this “localized opposition is more likely to be caused by an anticipated disutility associated with the loss of a neighbourhood charm, constituted by specific cultural amenities” (p. 31). In this sense, cultural and ‘intangible’ neighbourhood characteristics are just as relevant as threats of concerns about residents’ own displacement.

In order to explore the underlying forces of gentrification in Berlin, an de Maulen and Mitze (2014) have carried out a quantitative analysis of rental price dynamics. They conclude that Berlin is a subject of ‘endogenous gentrification’ where “high-income households gradually move to neighbourhoods with cheap housing prices but which border rich neighbourhoods in order to live close to other high-income households” (p. 325). Additionally, the urge of new middle- and upper-class residents to feed the aspirations of Berlin as a creative city has led to the construction of new-built luxury departments. These new developments “are understood as a powerful reworking of how the city, its uses and users are imagined and governed” (Marquardt et al. 2013, p. 1540) and conflicts with the aim of providing affordable housing.

This brings new dimensions to inequality. Huning and Schuster (2015) claim that this is a precedence of well-educated and employed middle classes over the poor, unemployed and deprived working class. In order to counteract this dynamic, squatting has surfaced as a movement towards urban restructuring in Berlin in a neoliberal real estate market (Holm and Kuhn 2011). Part of this movement of restructuring and urban renewal was observed in the fieldtrip in the squatting community of refugees situated in the Spreefeld area (see picture below). The author stresses the fact that these movements happen under a scenario of ‘multiplicity of gentrification’ with its historical ‘embeddedness’. This relates to the “interaction between top-down and bottom-up processes and their impact on urban development” (Huning and Schuster 2015, p. 752).

The issue of pressures on housing and infrastructure can be further illustrated by the provision of urban green spaces in Berlin. Rosol (2010) suggests that there is a political acceptance when it comes to projects organised in an autonomous way towards urban green space governance. I can relate these initiatives to the bottom-up squatting movements aimed to offset the spread of gentrification. Likewise, there has been an administrative structure that allows for an effective planning process for the entire city (Thierfelder and Kabisch 2016). This illustrates the top-down/bottom-up interaction explained in the last paragraph, which allows for the correct provision of urban green space in Berlin. Notwithstanding the fact that provision of urban spaces fulfil an acceptable per capita target, the distribution of such areas is not equally distributed if cultural backgrounds are taken into account (Kabisch and Haase 2014). This signals the need of a more equitable approach as gentrification has an effect not only on housing, but on the provision of other services such as green infrastructure, as aforementioned.

Creative cities: the road ahead

It is necessary to address the fact that the mobilisation of the ‘creative class’ and the gentrification arguably generated by them are not exclusive to the case of Berlin, but exist in cities around the world as a global phenomenon. For example, Novy and Colomb (2013) suggest similarities between the discursive issues in Hamburg and Berlin. The authors claim that in both cases the ‘creative community’ -understood as an urban social movement- has been co-opted by the official top-down marketed image of the creative city. This is in the same vein as Jakob (2010), who claims that it is necessary to rethink the creative city by placing equality, and not growth and centrality, in the centre of creativity as the engine of the Berliner economy. The author ventures on to claim that creativity should not only be a development strategy, but a human right towards personal fulfilment and happiness.

On the ground level, schemes such as co-housing projects can be an opportunity to address social inclusiveness in urban development and simultaneously be attractive to those in need of “affordable housing and working space” (Droste 2015, p. 87), such as members of the academic and creative milieus. Although German co-housing seems to be a relatively advanced feature of inclusive urban development, the co-housing project that we visited in the Spreefeld area showed that these can be subject to the very issue they try to deal with: gentrification. Most of us agreed that the co-housing project seemed to be inhabited by certain demographic groups that do not reflect the potential to address inclusiveness. Although the in-site explanation by Mr. Michael LaFont tried to cover the issue of inclusiveness and diversity, there was no evidence of those traits as we took a tour through one of the buildings.

What can be learned from the case of Berlin in terms of place marketing? First of all, (Colomb 2011) invites us to think over the question of uniqueness or representativeness of Berlin. The history that has shaped Berlin as we know it today is unique, but certain lessons can be taken from the German capital’s urban development if a proper balance of singularities is included in the analysis. I believe that Berlin can be considered as a paradigmatic city, especially for cities in the so-called Global South, as the planning regulations in developed countries environments often do not allow for some of the Zwischennutzung to happen. The feeling of informality and ‘unplanningness’ that defines Berlin as a creative city seems to be fertile ground in environments where planning systems are flexible.

In this sense, other countries have wanted to emulate the role of the creative city. Such is the case of Guadalajara, Mexico, that has been popularly described as the Mexican Silicon Valley. This includes the creation of Ciudad Creativa Digital, as a smart city project towards development of creativity and generation of content for the Spanish speaking countries. Carlo Ratti, the creator of the project, explains that this kind of project is a result of experimentation. However, I consider that this tactic is merely a top-down imposed approach that does not take the very heart of the city into account: inhabitants. No inputs from the residents of Guadalajara can be found in the urban development agenda of the creative city, as the new ‘entrepreneurial’ urban politics (Colomb 2011) has touched upon the city. In this essay, I explained that equality should be the centre of creative cities, and not economic growth. Guadalajara’s creative city approach is committing that mistake exactly by neglecting its inhabitants in exchange of commercial interests. The city of Guadalajara might have a natural feel of informality but specific conditions such as its socioeconomic conditions and urban dynamics are what define the applicability and success of place marketing in a city.

Conclusions

The ‘Berlin as a creative city’ discourse seems to be engaging in a self-fulfilling prophecy. As suggested by Colomb (2012), the discourse lives a dichotomy in which the symbolic value of Berlin as a creative city has been lifted but it has halted the very basic everyday conditions to sustain the creative process itself. The process seems to have reached a point of no return with the inevitable price of gentrification to be paid. As part of this gentrification, tourist-oriented low-priced facilities as opposed to basic services for the all-time residents seem to be the staple of development (Füller and Michel 2014). I believe that the discourse, which seems to have permeated to the long-term policy planning for the next 15 years, needs to be rethought. This new approach is to set equality at the centre of the creative city.

As for the empirical evidence from the fieldtrip itself, I consider those places that reflected the Zwischennutzung nature of Berlin as relevant visits to understand the informal and impermanent feel of the city that is very well related to the creation of spaces for creativity to occur. Moreover, the cohousing project in the Spreefeld area serves as an example of pop-up solutions to some of the issues generated by the behaviour of the housing market without ignoring the need for affordable housing and working sites. Be that as it may, accessibility should also be a central part of these solutions, given the pressures faced by the Berliners regarding displacement and valuable neighbourhood characteristics. Berlin seems to champion these practices but if this vision is to be applied anywhere in the world, caution should be taken in terms of the specificity of planning environments. Other cities in the world are following the example of Berlin as a centre of creativity and innovation. The case of Guadalajara, Mexico presented here, highlights the need to realign the objectives of a creative city towards inclusion and equity.

References

Ahlfeldt, G.M. (2010). Blessing or curse? Appreciation, amenities and resistance around the Berlin ‘Mediaspree’. Hamburg Contemporary Economic Discussions, 32.

an de Maulen, P. and Mitze, T. (2014). Exploring the spatial variation in quality-adjusted rental prices and identifying hot spots in Berlin’s residential property market. Regional Studies, Regional Science, 1(1), pp.310–328.

Bader, I. and Scharenberg, A. (2010). The Sound of Berlin: Subculture and the Global Music Industry. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 34(1), pp.76–91.

Balicka, J. (2013). Berlin, Zwischennutzung, Gentrification and Public Participation. Estonian Urbanists’ Review.

Colomb, C. (2012). Pushing the urban frontier: temporary uses of space, city marketing and the creative city discourse in 2000s Berlin. Journal of Urban Affairs, 34(2), pp.131–152.

Colomb, C. (2011). Staging the new Berlin; Place marketing and the politics of urban reinvention post-1989. London: Routledge.

Droste, C. (2015). German co-housing: an opportunity for municipalities to foster socially inclusive urban development? Urban Research & Practice, 8(1), pp.79–92.

Füller, H. and Michel, B. (2014). ‘Stop Being a Tourist!’ New Dynamics of Urban Tourism in Berlin-Kreuzberg. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 38(4), pp.1304–1318.

Holm, A. and Kuhn, A. (2011). Squatting and Urban Renewal: The Interaction of Squatter Movements and Strategies of Urban Restructuring in Berlin. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 35(3), pp.644–658.

Huning, S. and Schuster, N. (2015). ‘Social Mixing’ or ‘Gentrification’? Contradictory perspectives on urban change in the Berlin district of Newkölln. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 39(4), pp.738-755.

Jakob, D. (2010). Constructing the creative neighborhood: Hopes and limitations of creative city policies in Berlin. City, Culture and Society, 1(4), pp.193–198.

Kabisch, N. and Haase, D. (2014). Green justice or just green? Provision of urban green spaces in Berlin, Germany. Landscape and Urban Planning, 122, pp.129–139.

Marquardt, N. et al. (2013). Shaping the Urban Renaissance: New-build Luxury Developments in Berlin. Urban Studies, 50(8), pp.1540–1556.

Novy, J. and Colomb, C. (2013). Struggling for the Right to the (Creative) City in Berlin and Hamburg: New Urban Social Movements, New ‘Spaces of Hope’? International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 37(5), pp.1816–1838.

Polinna, C. (2017). Current challenges and topics of urban development in Berlin.

Rosol, M. (2010). Public Participation in Post-Fordist Urban Green Space Governance: The Case of Community Gardens in Berlin. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 34(3), pp.548–563.

Senate Department for Urban Development and the Environment. (2013). BerlinStrategy. Urban Development Concept: Berlin 2030. [online]. Available from: http://www.stadtentwicklung.berlin.de/planen/stadtentwicklungskonzept/download/strategie/BerlinStrategie_Broschuere_en.pdf.

Thierfelder, H. and Kabisch, N. (2016). Viewpoint Berlin: Strategic urban development in Berlin – Challenges for future urban green space development. Environmental Science & Policy, 62, pp.120–122.