This article is based on my research focus in my time as a Local Pathways Fellow with SDSN Youth. The idea of improving walkability in Los Reyes / La Paz in Mexico City by colouring pedestrian crossings was also nominated by Columbia University as one of the best 100 projects for the Local Project Challenge.

Even though the official Walk Score for Mexico City is at 100% (Walkscore, 2019), the city is not very walkable. It is certainly not a walker’s paradise, as stated on WalkScore website. The reason behind this discrepancy between reality and the walkability score is that the score looked only at city centre. If you venture out to the city’s surrounding areas, however, you will quickly see that pedestrians have very low priority. Streets are stuffed with cars, motorbikes, buses, mini vans and many other modes of transportation. Pedestrians have to make their way on badly designed sidewalks which are overcrowded, mostly filled by informal vendors or simply non-existent. Crossing a street in Mexico City can take up to 15 minutes. Traffic lights for pedestrians are the exception, and in many cases, you have to climb stairs to cross on a flyover for pedestrians, which is only suitable for young and healthy pedestrians who are not carrying a big load. Any other person will struggle.

The need for more pedestrian safety

About half of Mexico City’s traffic victims are cyclists and pedestrians (CONAPRA 2017). Mexico is in the global top 10 of traffic victims (WRI 2019). The interventions planned by the government are focused on city centre, which also points to Mexico City’s main urban planning challenges: Officially, only 8 million people live in this city. However, the urban conglomeration is home to another 17 million. They officially fall under the legislation of the Estado de México, which is another state. However, this state is not equipped with the infrastructure, finance or knowledge to deal with a mega-city. This results in large inequalities between central Mexico City and the margins of the capital.

At the same time, there are some attempts at a solution. These are focused on city centre, where walkability is already much better, but it still is a good start. For examples, projects have already managed to create more space for pedestrians by colouring zebra crossings, creating new crossings and making the existing sidewalks wider. One of the country’s largest paint companies (Comex) supports this kind of project. What is lacking is the support of urban planners. With very little work, this urban intervention could be a starting point in demanding better pedestrian conditions.

The Government’s Mobility Plan

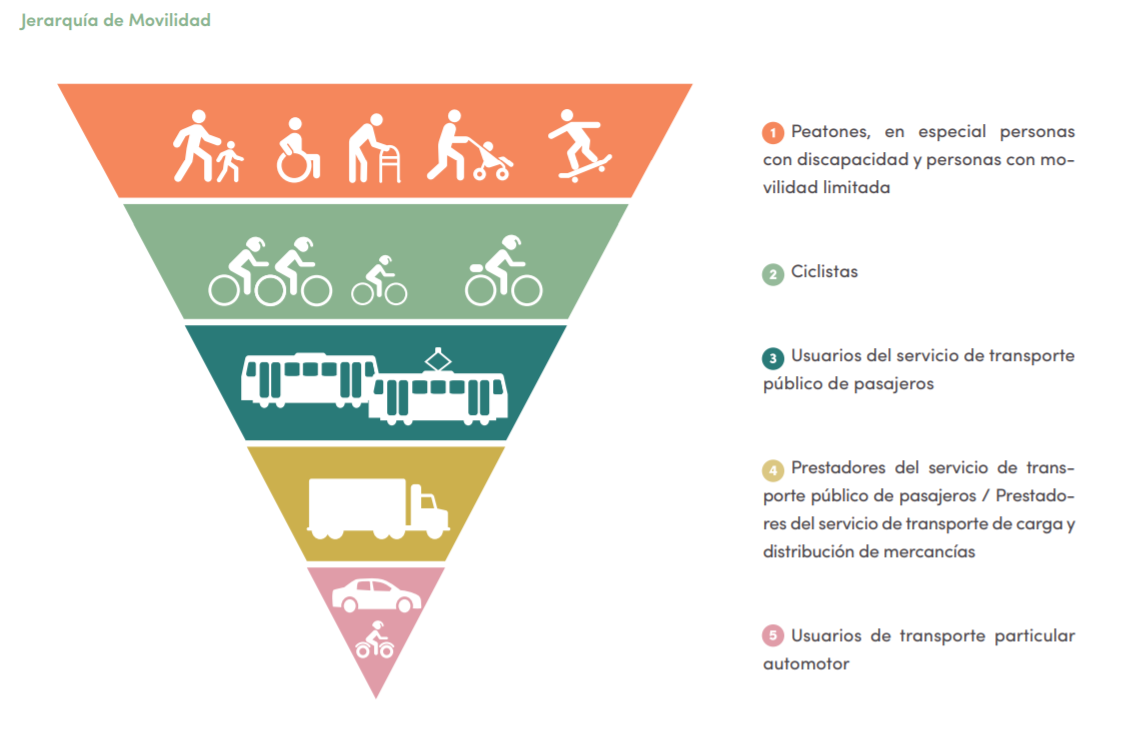

Officially, Mexico City’s government is dedicated to improving pedestrian safety. The Secretaría de Movilidad (SEMOVI), Mexico City’s transport office, has a strategic mobility plan for 2019 (SEMOVI 2019), which admits that the current infrastructure in many parts of the city is hostile towards pedestrians and cyclists. They are planning on doing interventions like the one you can see in the picture in 32 street crossings in Mexico City, and this process has already started.

However, this strategy is entirely focused on city centre, where walkability is already much better than in the outskirts or even the central, but poorer parts of Mexico City. 40 additional km of cycle lanes and 15 improved pedestrian bridges are also part of the programme, but in a city with about 25 million inhabitants, this seems to be not more than a drop on the hot stone.

Interestingly, there is even a fund for pedestrian projects (Fondo para el Taxi, la Movilidad y el Peatón de la Ciudad de México), but the official SEMOVI report admits that it has been very opaque and apparently not very operative.

This means that while Mexico City’s current government is aware of the challenging situation for pedestrians, it is only committing to minimal measures. Financing is unclear and the already marginalised areas of this metropolis, many of which have unclear governing situations, are not benefiting at all from the ideas. At the same time, the new urban policy for Mexico City has not been published yet. Elections happened one year ago, in July 2018, but the new government only started its work in December 2018. For Mexico City, we can expect an urban policy by the end of 2019. Meanwhile, urban initiatives stand still.

Community Action for Improved Walkability

At least, they stand still on the political or top-down level. I am fascinated to see bottom-up initiatives happening in many boroughs, where people get together to create their own solutions. If they take the idea of improving pedestrian walkways and crossings, they have more leverage in participating in the new urban policy of Mexico City. At the same time, the frustration with corruption and lacking political will leaves no other option for citizens who have been waiting for the government to improve their streets and sidewalks for many years.

The example of ENSAMBLE’s work in community activation and encouragement shows that where government is not delivering, citizens’ initiatives are needed and welcome. Improving walkability in Mexico City is therefore a challenge for each neighbourhood – at least for now. At the same time, innovative initiatives can attract media attention and therefore influence government. I will keep you posted on updates about the new urban policy for Mexico City, and other interesting stories from Mexico’s capital!

SuSana Distancia: The Mexican Superhero Fighting the Spread of Coronavirus

#sdg11inmexicocity: Does Greening a Highway Make It Environment-Friendly?

References

CONAPRA. (2017). Informe sobre la situación de la seguridad vial en México 2017. México: CONAPRA

Ensamble (2019): Los 500 x La Paz. Available online at https://www.nsmbl.org/programas-1

SEMOVI (2018): Programa de Mediano Plazo “Programa Integral de la Seguridad Vial” 2016-2018 para la Ciudad de México. Available online at https://www.semovi.cdmx.gob.mx/storage/app/media/PISVI_Low.pdf

SEMOVI 2019: Plan estratégico de movilidad de la Ciudad de México: Una ciudad, un sistema. Available online at https://semovi.cdmx.gob.mx/storage/app/media/uploaded-files/plan-estrategico-de-movilidad-2019.pdf

Walkscore (2019): Mexico City. A Walker’s Paradise. Available online at https://www.walkscore.com/score/+mexico%20city++

WRI (2019: ¿Cómo pueden México, y las ciudades de Latinoamérica y el Caribe atender el grave problema de la inseguridad vial? Available online at https://wrimexico.org/bloga/%C2%BFc%C3%B3mo-pueden-m%C3%A9xico-y-las-ciudades-de-latinoam%C3%A9rica-y-el-caribe-atender-el-grave-problema-de