How do women participate in cities? Are they visible in public spaces and do they actively shape the urban landscape?

Lately, I have been thinking a lot about these questions. Living in a Middle Eastern neighbourhood of Manchester, I often feel like I am in a different country. This is very enjoyable, apart from the many occasions when I am the only woman around. The countless supermarkets, barber shops, shisha bars, restaurants etc. are mostly occupied by men. I often feel observed, stared at, flirted at and, mostly, annoyed. My experience here makes me think about how women in public spaces are perceived very differently in different cities across different cultures. I was also inspired by a lecture by Ms Sylvia Chant, that I attended on Women’s Day. She talked about gender inequalities and injustices in cities of the Global South (although I would add that to a certain degree, they are also omnipresent in Northern cities). She showed a video of what it is like to simply walk across a bridge in Cairo as a woman:

These instances of sexual harassment or even abuse happen to women everywhere, but they are most common in male-dominated spaces. The danger of (often sexual) violence and gender-based harassment is among the most common reasons for women to avoid public spaces, often leaving large areas of cities to men. However, don’t you agree that public spaces should be for everyone, regardless of age, nationality, religion, sexual orientation and – yes! – gender?

The design of public spaces

So, let’s talk a bit about public spaces. Public spaces are like the living room of a city. They are open and accessible social spaces, such as parks, squares, waterfronts, market places, malls and streets or pavements. According to the American Planning Association, “great public spaces” should promote human contact and community involvement, as well as reflect local culture and a place’s special character. They should be safe, welcoming, accommodating and visually attractive (read more).

Personally, I have grown up with a certain sense of entitlement when it comes to public spaces – of course I can use them without even thinking about being a woman, whenever I like, alone or with friends, and without being disturbed, stared at or harassed in any way. However, this is sadly very different for so many women who often avoid public spaces in order to be safe and maybe even because they don’t feel entitled to these spaces.

Reading more about the topic, this quote caught my eye:

“The number of women that appear in the public realm, during the day and especially at night, is an indicator of the health of a society and the safety and livability of a city. The more that the built environment is designed with women in mind, the more women will feel safe, welcome and comfortable using public space and the more livable a city will be for everyone.” (by Smart Cities Dive)

How to improve public spaces for women?

How, then, can public spaces be improved so that they are safer and more comfortable for women to use? I have collected different ideas from cities around the world:

Planning measures

Urban planners are responsible for creating safe and attractive public spaces that increase the quality of a city. Often, this is closely linked with transportation that happens in a public space or is connected to them (i.e. the walk home from the metro). In Delhi, as well as in Japanese cities, authorities introduced

women-only metro carriages. Female guards take care that no men enter these carriages and women have a specific waiting area on the platform. However, while this makes waiting for and riding on the train safer, the way home or the way to the metro station can still be very dangerous for women. This is more of a palliative solution, but it is crucial that urban planning changes basic designs in order to make cities safer and more attractive for women. This includes busy public spaces and streets, safe public toilets and parking spaces and giving priority to pedestrians. It is also very important to consider women’s different use of the city. They are very often the main caretakers of children, which means that playgrounds, nappy changing facilities and enough room for strollers are essential to make public spaces more convenient for women. Studies have found that women walk more than men and travel through the city with many different purposes, while men mostly use the same routes to travel to and from work (read more on these travel patterns here).

Educational measures

To go a step further, experts recommend educational measures change the perspectives of both women and men on how public spaces can or should be used. Of course this is often done (or should be done) by planning authorities, but here are some fascinating examples grassroots initiatives, run by women who took it upon themselves to make a statement and create more awareness of the existing gender gap in public spaces.

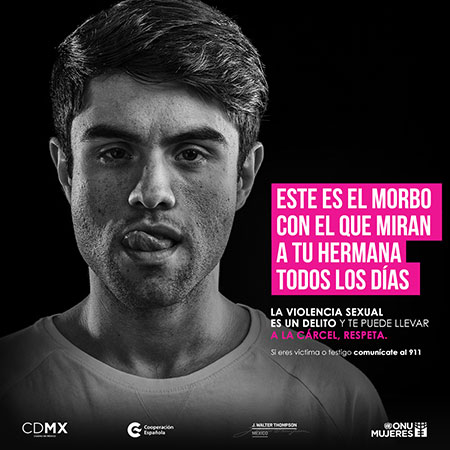

In Mexico City, UN Women partnered with the transportation network to create an experience specifically for men, showing them what it can be like to use public transportation as a woman: For example, a plastic penis was installed on some seats in the metro to make travellers reflect about physical harassment and manspreading.

In addition, countless posters like the one shown on the left were put up all over the city. It says ” This is how morbidly they stare at your sister every day”. Search for #noesdehombres on Twitter to see more examples!

In self defense classes or on websites like Hollaback, women learn what to reply to verbal abuse of all kinds, which is sadly all too necessary in many cities.

My favourite example of talking back in order to change the perspective of perpetrators is “Stop Telling Women to Smile”, an art project by Tatyana Fazlalizadeh. She records women’s stories of harassment and, importantly, the women’s replies. She then paints the women and what she would like to say to the person who harassed her on a poster and puts it up close to the site where the harassment happened. Watch this short documentary to learn more about her work:

These examples show that women are most concerned with harassment and violence. Thanks to social media, it is now easier than ever to immediately name and shame perpetrators, call for help and create solidarity among women. An initiative from Pakistan is mastering this, using the simple Twitter hashtag #girlsatdhabas. The tea houses, dhabas, are traditionally used by men exclusively, but this group of girlfriends started posting pictures of themselves at dhabas on social media. Read an interview with the founders of Girls at Dhabas here. This is a great example for how social media can be used to create momentum and raise awareness for women’s presence in public spaces.

Women and participatory planning

Digging even deeper, I believe that apart from planning and educational measures, there needs to be a different approach to planning, combined with a shift in perception. Public spaces that are safe and comfortable for women to use can only be truly implemented with more women in planning and the explicit participation of women in planning. Again, participatory planning techniques come in by learning from women what they need and what can be improved in existing public spaces.

Coming back to the initial questions, this could make women be more present in public spaces and give them a way to actively shape the urban landscape by participating in planning processes. Of course this also depends a lot on local culture and tradition as well as women’s education, but here again social media and modern technology can play a crucial role in gauging female opinions.

In an article about women’s right to the city, Urbanet points out how women have shaped cities since the beginning of urbanisation, which should entail the right (or entitlement) to use the advantages of cities like public spaces.

“The question of how people use and enjoy urban goods is linked to citizen rights, such as rights to services, infrastructure, transport, security, and recreation, among others. Therefore, the question of equal access and usage is not only about spaces as physical places, but also as symbolic and political sites of dispute about how individuals or groups of people inhabit the cities they live in, and who uses urban spaces.” (Urbanet)

Do you have any ideas on how women can participate more in cities and place-making? Please share your thoughts and ideas in the comment section below and don’t hesitate to contact me (laura@parcitypatory.org).

Header copyright: own picture