In this introductory text, I explain the rather idealistic, but fascinating use of participation in urban planning.

What is urban planning?

What does the term “urban planning” make you think of? Probably a bunch of men with important plans who work together with architects to design a city. Their job is often considered to be quite technical and a bit boring, but on the contrary! Urban planners do the whole layout of a city and decide what goes where and why. They follow a detailed process from identifying and defining an urban planning problem, creating a vision to guide design scenarios, developing innovative solutions and making a coherent plan for the implementation of this solution. After implementation, a good follow-up is required.

“Town and country planning might be described as the art and science of ordering the use of land and the character of siting of buildings and communication routes so as to secure the maximum practicable degree of economy, convenience and beauty” (Keeble,1952)

For a long time, urban planning has been done mainly by the planners in cooperation with the respective city. This is of course a very efficient and fast way of working, but what about the people living in cities? Aren’t they the best planners because they know their own needs and have countless ideas on what should be where? Still, they often don’t get asked at all and just have to live with the consequences of new buildings or infrastructure in their city.

This is why I advocate for participatory urban planning, meaning that the planners include the whole community or neighbourhood in the planning process. This grassroots approach increases the legitimacy of new urban developments – who could better judge plans and contribute additional ideas to urban planning than the people living in a neighbourhood? The aim is to find a consent or satisfactory compromise between the many different interests and conflicting groups that make up a neighbourhood. Together, alternative or new ideas are developed.

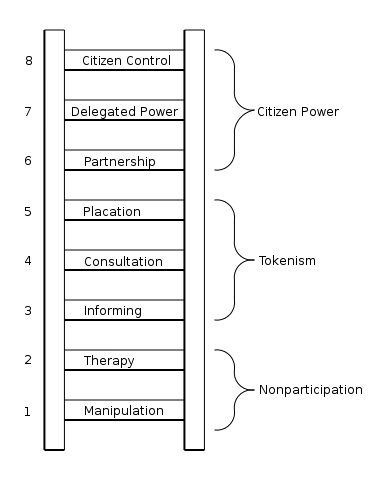

All too often, when we hear about participatory planning it is a perfunctory exercise, done because it is required by the UN or condition for receiving development aid. This often entails only a signature or a consent of someone from the community in question. But only the consent of as many people as possible makes it community participation and thereby participatory urban planning. Without this, participation is more tokenism or even manipulation (non-participation). This is famously described in Sherry Arnstein’s 1969 article called “A Ladder of Citizen Participation”:

Main challenges in achieving citizen power are how to include all sections of community and how to integrate the preferences of different social groups. Often, a lack of follow-up decreases credibility. As always, a lack of funds to actually implement the plans from the participatory planning process can be deadly to the project. There are many different versions of participatory planning and political will plays a great role in implementing the results of the participatory process.

At this point in urban planning practice in developing countries it seems most important to introduce real participatory methods. There are different approaches to participatory urban planning and I want to give you a short overview. Many more ideas are to come in following blog articles, but here are the main approaches to participatory urban planning:

Participatory Rural Appraisal (PRA)

This is the most famous approach to participatory planning, rural as well as urban. It was basically thought of by Robert Chambers, a British development scholar. He defined the following principles for PRA facilitators:

- Handing over the stick (or pen or chalk) to locals

- Self-critical awareness of facilitators

- Personal responsibility

- Sharing using photocopies or more modern methods

Based on these principles, PRA is often facilitated by an outside expert who listens to locals as teachers and experts and considers himself or herself the student. There are many different methods to do this, including time lines, trend analysis, mapping, presentations etc. The techniques of PRA rely on oral communication and the use of pictures whenever possible to include dyslexic people. The aim is for locals to clearly define their problems and identify possible solutions.

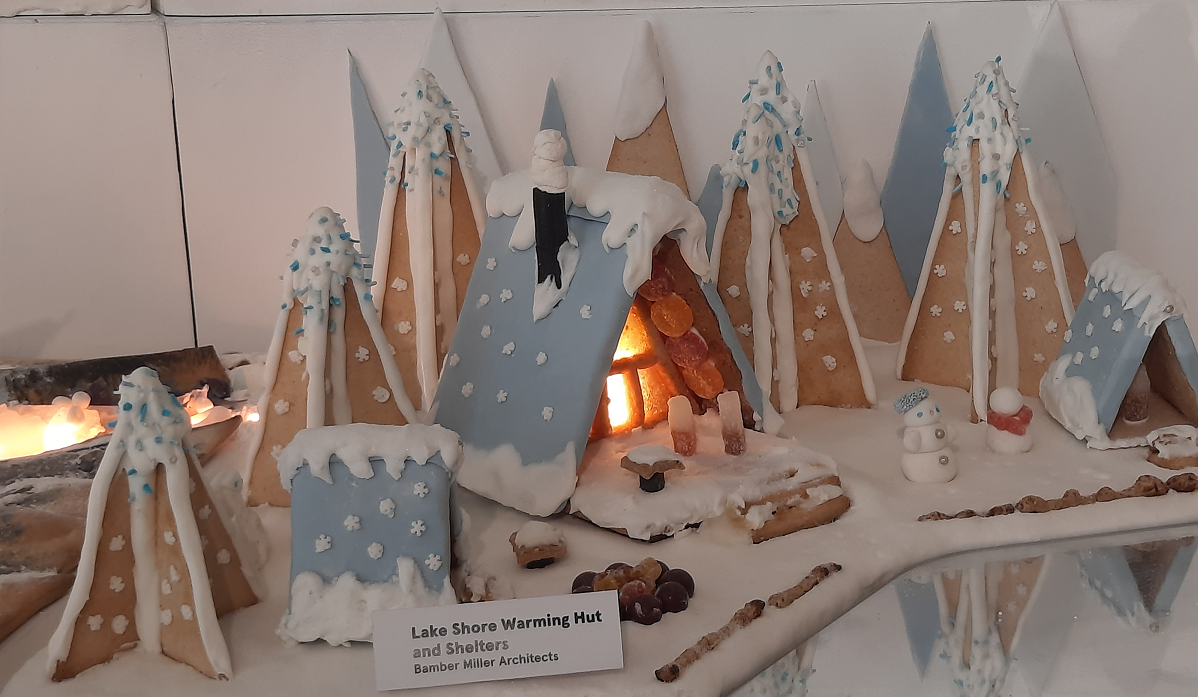

Planning for Real

Planning for Real (PFR) was developed in the United Kingdom and is a rather new community planning process. It is based on a “3D model” (see picture above) of the neighbourhood. Residents work together on local issues and identify challenges and priorities. In cooperation with local agencies, a plan for action is developed. The 3D model is part of the whole process and is always being referred to. Different cards and notes can be placed on the model in the process to collect ideas. These are then laid out on a chart to categorise them into “now”, “soon” and “later”. Once these priorities are clear, facilitator ask each family of the community what they are good at and how they can contribute to improving their neighbourhood. This often leads to astonishing results at a very low budget.

Participatory Mapping

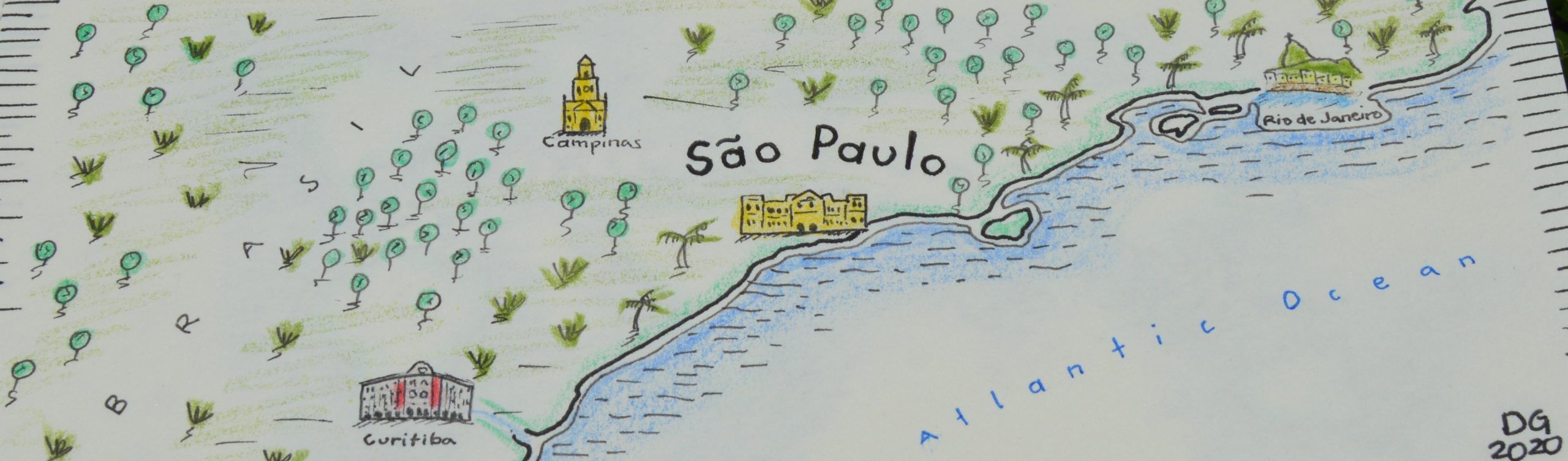

“Maps are more than pieces of paper. They are the stories, conversations, lives and songs lived out in a place and are inseparable from the political and cultural contexts in which they are used.” (Warren, 2004)

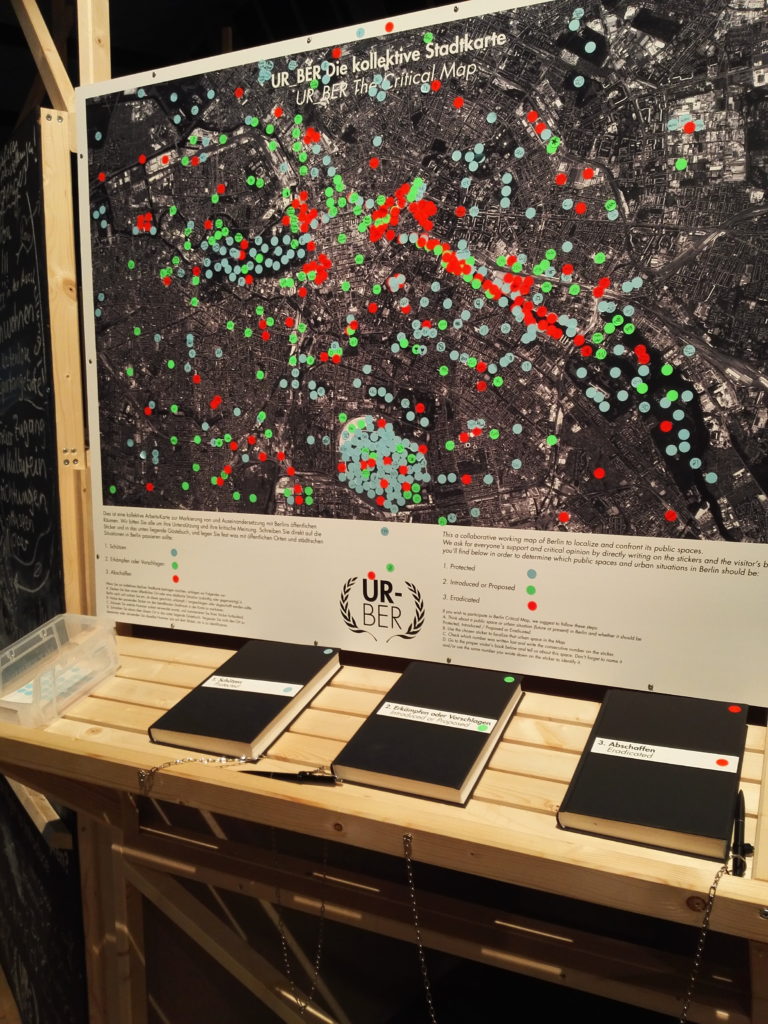

Participatory mapping is a tool for, but also an approach to participatory urban planning. Modern cartography tools are combined with the spatial knowledge of local residents who draw or create a map of their neighbourhood. Thereby, new information can be discovered that is often not visible on Google Maps or other conventional maps. It is possible to highlight certain elements, problems or social issues on these maps. Often, traditional boundaries, access to resources, sacred places and other culture-specific topics are depicted very well on these maps.

Apart from the technical process of creating the map, this approach also serves to give participants a space to discuss given or new planning issues. By observing the discussion, a new understanding of social connections and organisation can be gained.

Apart from maps, there are also diagrams, models, transects and other visualisations that work in a very similar way.

E-Participation

I am currently working on a paper on e-participation – read some of the results in this blog post! The concept of using Information and Communication Technologies (ICT) to enable participation is rather new and connected to the smart city trend. By engaging the citizens in online debates, polling and other activities, the municipal government and the urban planners get a broad idea of trends and needs. However, e-participation is only available to those who can read and have internet access, making it a rather elitist tool. Also, e-participation is mainly useful to get some input and feedback from citizens, but it is very hard to create a truly participatory process.

Conclusion: Understanding communities

When going through a participatory planning process, the two most important questions to keep in mind are: Who initiates the participatory project? Who will benefit ultimately?

From what I have learned so far, the most important thing in participatory urban planning, whether you start it as an outside consultant or as a local leader, is patience and understanding. You have to be able to establish an open, respectful dialogue and take a lot of time to discuss with and understand all relevant stakeholders. It is important to reach as many people as possible, meaning that you have to consider disadvantaged groups, while simultaneously accounting for elite interests. A prerequisite for participation to happen again and again is that there are at least some tangible results from the first try. Otherwise, some community members might be annoyed that you wasted their time and effort.

Participation is never going to be perfect and you are still likely to exclude some people from the planning process. It is also a very slow process. Still, including community members in the urban planning process makes for better and more liveable cities. Or to put it in the words of the great urbanist Jane Jacobs:

“Cities have the capability of providing something for everybody, only because, and only when, they are created by everybody.” (from The Death and Life of Great American Cities, 1961)

Are there any participatory planning approaches in your city? Do you think that participatory urban planning is a viable approach? Please share your thoughts and ideas in the comment section below and don’t hesitate to contact me (laura@parcitypatory.org).

(Picture rights for the header image: Planning for Real 058 by Katy Wrathall via flickr, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)