Interview with Amy Hubbard, Co-founder/Practice Lead, Capire Consulting Group

Amy Hubbard of Capire Consulting Group has over 20 years’ experience in community engagement and public participation. Undergraduate study urban planning and social policy; Master’s in international urban and environmental management.

In my first year working as a planner, I realised something was missing from the widely accepted approach to strategic planning in Australia. While we were consulting with stakeholders (mostly influential people and organisations), the public were missing from the conversation. This didn’t seem right or just to me; as the public are those who would ultimately be the users, or benefactors of the new places and spaces being planned. The best people to design a space are those that will use it.

I have always approached community engagement with a lens of diversity and inclusion. I have always felt strongly that if you can’t hear all the voices, then you’re not trying hard enough. All people will participate in engagement if you design the process to reflect their needs and values.

As people creating better cities, we have a responsibility to design spaces and places for all members of the community, not just those with louder voices.

There are a lot of participatory urban planning initiatives in Melbourne – which one is your personal favourite?

My personal favourite is ‘Return to Royal Park’.

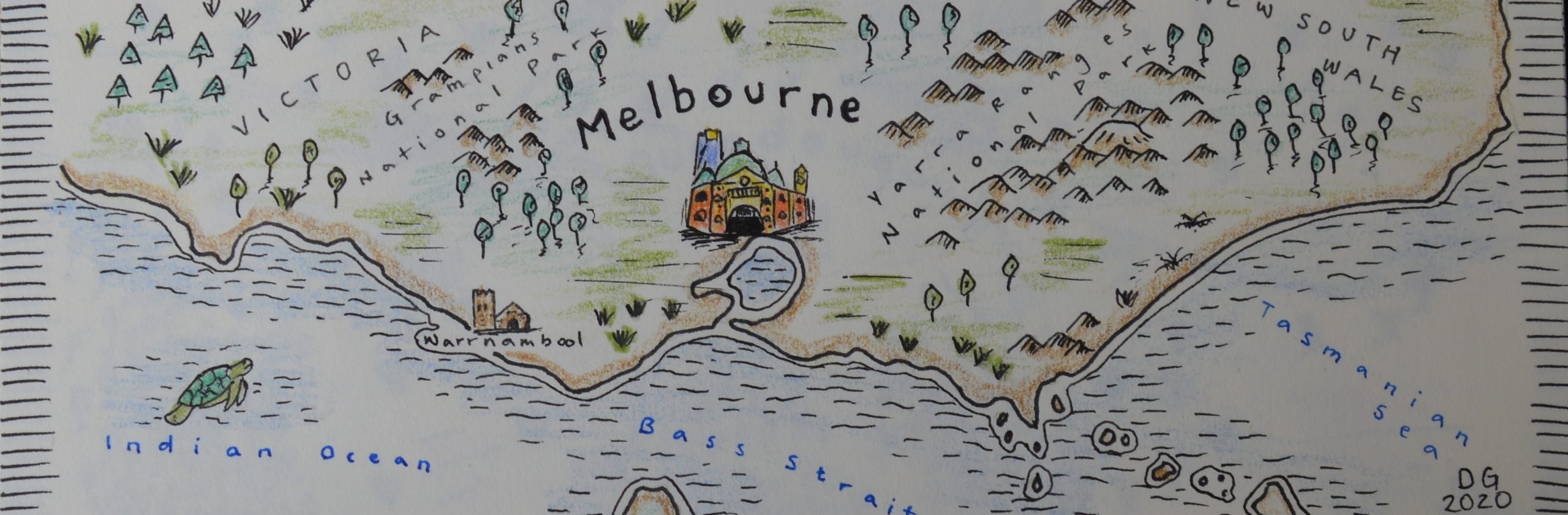

In 2012-13, Capire was engaged by the City of Melbourne to facilitate community engagement to design a new ‘green’ space on a site adjacent to Melbourne’s Children Hospital and within the boundary of the city’s largest park, Royal Park. The project presented a very unique opportunity to establish a new parkland in the centre of the city.

Capire designed and delivered three phases of public engagement to collaboratively identify the form and function of the new park. There were many conflicting views and some very dominating opinions early in the process; from “no change over my dead body” to “how about a water park?”. However, nature-based play was identified early as something that most members of the community wanted to see included.

Participants included housing tenants, hospital workers, patients and their families, established resident groups, traditional owners, members of the public, rough sleepers and local children. Our toolkit was extensive; from focus groups with newly arrived migrants; workshops in local schools; interviews with rough sleepers; and public forums of 50+ vocal community members.

We used face-to-face and digital engagement to provide multiple opportunities for people to participate and stay connected to the design process. Through the engagement we were able to take the community on a journey through sharing of stories and ideas; to the development of a series of ‘community inspired design principles’; to the creation of an ideas plan which plotted the principles and their ideas; and a concept plan.

Approximately 700 community members and 150 children shared their ideas, vision, and preferences for the site through the engagement process.

I loved the project because of the diversity of people, views, and values. Through the process we were able to find common ground where they listened to each other, balanced their own needs with the broader community and worked together to create the principles. I also loved that the City of Melbourne and the other project partners really invested in the process and recognised early on that the engagement could have a range of purposes including participatory design, community strengthening and education.

Since opening in 2014 the new park has been full of children – from the local neighbourhood, public housing tenants, the nearby hospital, as well as families who travel from all over the city.

In your work, which methods for participatory planning have been most successful?

I always find the most successful processes, are those where we have time and space to go deep into the context, opportunities, and limitations before arriving at a solution. From my experience, these processes are generally a series of workshops, which build on each other and work towards the agreed outcomes. Workshop participants represent the diversity of the community and a broad range of interests in the community; from those ‘usual suspects’ to the homeless, the newly arrived migrants, people with the disability and children. People have the time to hear from each other; hear from specialists and experts; to weigh up options; and to arrive at a solution together.

What challenges have you encountered in trying to foster community engagement, and how have you overcome them?

There are so many challenges. One major challenge is that many people working in planning and policy still consider community engagement as a ‘tick the box’ exercise. This means they are not vested in the process or the outcomes and are really just going through the motions. Also, people not recognising that you need different tools for different types of people and conversations. Still people think a survey (just a survey) is all you need to engage the whole community. Finally, leaders not listening to the findings or outcomes of the engagement. It undermines the whole processes and diminishes any trust between decision makers and their communities.

How do you work with CALD (culturally and linguistically diverse) communities in Melbourne? What challenges do these communities have in terms of participation?

Firstly, we always ask the group how they would like to participate. We don’t assume – even when we have engaged with the same cultural group before. We often work with leaders to help open up and facilitate conversations with groups; and we often attend their meetings and festivals (we go to where they are). Often we train members of the cultural groups as ‘engagement champions’ and they work along our team to deliver the engagement process. We also disguise our engagement as something else – is it a market stall? Is it a game? Is it an art installation? No, it’s community engagement.

Some of the challenges include lack of understanding of the purpose or intent of engagement; lack of trust in the process, leaders and other community members. I learnt very early on that in some languages, a direct translation of ‘engagement’ is ‘propaganda’.

Does your work continue in Covid-19 times? If so, what tools do you use to enable virtual participation – or have you found a way to continue with community engagement offline as well?

We continue to work during Covid-19, and we’ve never been busier. We had to adapt very quickly and have been combining virtual engagement through forums like Zoom, digital engagement through platforms like EHQ and old school techniques like hard copy mail-outs, SMS messages and a project ‘hotline’. We have had to be creative with our tools to ensure our processes are accessible for all. We have been working hard to make sure our process is inclusive, breaking down engagement barriers by building digital literacy and providing some community members with reliable access to the internet (for example).

Back in April 2020 I delivered a full day studio for a group of master’s students which focused on community engagement and a small public park. I was really nervous going into the workshop and didn’t believe I could build the same rapport and energy with participants. The studio was my ‘a-ha’ moment; when I realised most things can be adapted to a digital or virtual space and that people can have a very similarly rewarding experience.

In your opinion, what needs to improve in Melbourne in order to have a better culture of community engagement and participatory planning? Or would you say that the situation is already good in comparison to other cities?

Melbourne has a very good culture of community engagement and participatory planning, but there are always opportunities for improvement. To ensure government takes it seriously, I think principles of participatory planning should be included in the relevant legislation and planning policy. At the moment it does include engagement but more in the form of consultation. While at least this is a start, it doesn’t give the community an active voice or any real power in the dialogue of creating new spaces and places. I believe this will come in the future as Victorian legislation focusing on other aspects of governance and civic life has been updated to include provision for public deliberation.

Thank you, Amy!